Steamboat Dispatch

September 1906 Edition

By Our Esteemed Correspondent, Mortimer Quibblequill

The Spirit’s Symphony: Charles Ives and the Spectral Conundrum

**MERRILL, N.Y.**—Charles Ives, the notorious musical prodigy and occasional madman, has once again returned to the haunted waters of Chateaugay Lake, where the very air seems infused with the echoes of spirits long forgotten. It is said that, even now, the Wendigo stirs in its ancient lair, summoned by a man whose obsession with the otherworldly might very well prove his undoing.

The good citizens of Merrill have long whispered of the eerie melodies that rise unbidden from the lake at the dead of night—sounds so dissonant, so unearthly, that they have driven many a summer visitor to the brink of madness. None, however, have dared to confront these spectral symphonies head-on, save for one man: Charles Ives.

A composer of great renown—or so he believes—Ives has taken it upon himself to capture the essence of the Wendigo in a symphony that defies description. “The Spirit’s Symphony,” as he calls it, is not merely a work of music, but a conduit through which the ghostly voice of the Wendigo speaks. Or so he claims. Whether this voice is one of divine inspiration or pure lunacy remains to be seen.

Accompanying Ives on this mad endeavor is his ever-skeptical guide, Nathaniel Collins, a man who has spent a lifetime navigating the treacherous wilderness of the Adirondacks. Collins, who has seen more than his fair share of fools and fortune-seekers, regards Ives with a wary eye, ever mindful of the dangers that lurk in the shadows and bogs of ChateaugayLake.

“Ives ain’t right in the head,” Collins muttered to this correspondent, as he loaded provisions onto a creaking steamboat, the *Misshapened Melody*. “Man thinks he can catch the Wendigo in a bottle, like some kind of cursed genie. But that ain’t how these things work. Spirits like the Wendigo… they don’t take kindly to bein’ trapped in music. They take it as an insult.”

And indeed, the Wendigo’s displeasure soon became apparent. As Ives began to compose, sitting at an ancient piano in the drafty confines of his lakeside cabin, strange things started to happen. At first, it was merely the music itself—notes that twisted and contorted in ways that defied human comprehension. But as the days wore on, the line between composition and possession grew ever thinner.

His once-methodical approach to music gave way to frenzied outbursts, each more erratic than the last. Ives would play for hours, his hands moving across the keys as if guided by some unseen force. The melodies that emerged were unlike anything he had ever written—discordant, jarring, filled with an unnatural energy that seemed to pulse with a life of its own.

It was as if the Wendigo itself had taken control of his mind, forcing him to transcribe its terrible voice into music. And the more he played, the stronger the Wendigo’s presence became, until it was no longer just a voice in his head, but a living, breathing entity that inhabited every corner of his world.

In his madness, Ives began to believe that the Wendigo was not merely a spirit, but a composer in its own right—an ancient, malevolent force that sought to use him as a vessel for its dark symphony. The more he resisted, the more powerful the Wendigo’s influence became, until Ives could no longer distinguish between his own thoughts and those of the spirit.

It was around this time that the Steamboat Dispatch received a series of increasingly incoherent letters from Ives, each one filled with cryptic references to “The Wendigo’s Cantata” and “The Devil’s Overture.” In these missives, he spoke of shadowy figures that appeared at the edge of the lake, their faces obscured by the mist, and of ghostly voices that whispered secrets in his ear as he slept. His correspondence with other composers—men and women of great genius and even greater eccentricity—took on a similar tone.

One particularly disturbing letter, addressed to the famed conductor Maestro Grisly Grimalkin, spoke of “harmonic poltergeists” that had begun to manifest in Ives’ cabin, wreaking havoc on his already fragile mind. Grimalkin, himself no stranger to the macabre, responded with what could only be described as cautious enthusiasm, urging Ives to “embrace the madness” and “allow the Wendigo to complete its symphony.”

But it was not until the arrival of Dr. Erasmus Eldritch, a self-proclaimed expert in “auditory phantasmagoria,” that the true extent of Ives’ affliction became apparent. Dr. Eldritch, a man of questionable credentials and even more questionable sanity, was summoned to Chateaugay Lake by Collins, who hoped that the good doctor might be able to exorcise the Wendigo from Ives’ mind—or, at the very least, convince him to abandon his perilous project.

Upon his arrival, Dr. Eldritch immediately set about diagnosing Ives with a condition he dubbed “melodic possession,” a rare and highly contagious affliction that, according to the doctor, could only be cured by playing the Wendigo’s symphony to completion. This cure, however, came with a dire warning: should Ives fail to complete the symphony, the Wendigo would consume his soul, leaving behind nothing but a hollow shell of a man, doomed to wander the shores of Chateaugay Lake for all eternity.

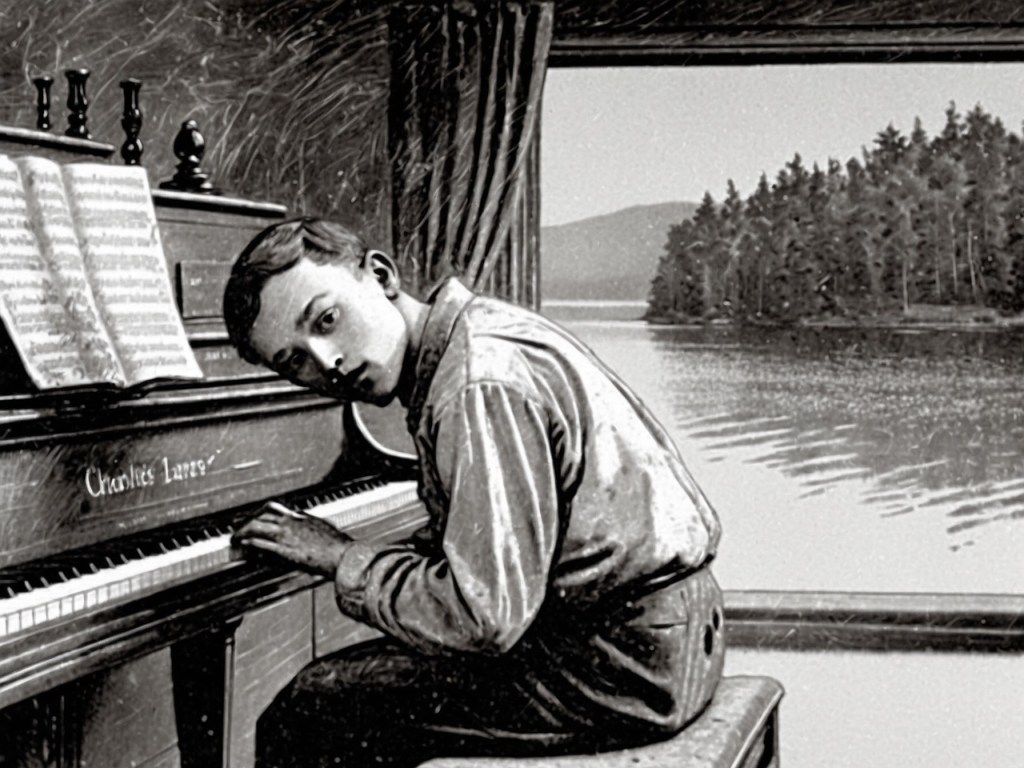

Despite these ominous pronouncements, Ives pressed on, driven by an insatiable need to finish the symphony that had come to dominate his every waking moment. Days turned into weeks, and still, the music flowed from his fingertips, each note more twisted and tormented than the last.

But as the symphony neared its completion, something strange began to happen. The very air around the cabin grew heavy with an oppressive silence, as if the world itself was holding its breath, waiting for the final, terrible crescendo. The Wendigo’s voice, once so powerful and all-consuming, began to fade, replaced by an eerie, otherworldly stillness.

And then, at long last, Ives played the final note.

For a moment, there was nothing—just the soft whisper of the wind through the trees, and the distant lapping of the lake against the shore. But then, as if in response to the symphony’s completion, a low, mournful wail rose from the depths of Chateaugay Lake, a sound that sent shivers down the spines of all who heard it.

The Wendigo, it seemed, had been appeased. But at what cost?

Ives emerged from the cabin, his face pale and drawn, his eyes hollow and sunken. The man who had entered Chateaugay Lake with dreams of capturing the spirit of the Wendigo was gone, replaced by a mere shadow of his former self. The symphony, now complete, had taken its toll, and the price of that completion was nothing less than Ives’ very soul.

As for the symphony itself, it remains a mystery, locked away in a trunk that no one dares to open. Some say that the music contained within is cursed, that to play it is to invite the Wendigo into your own soul. Others claim that the symphony is a work of unparalleled genius, a masterpiece that transcends all known forms of music. But whatever the truth may be, one thing is certain: the Spirit’s Symphony is a work born of madness, and its legacy will haunt the shores of Chateaugay Lake for generations to come.

And so, dear readers, we leave you with this cautionary tale—a story of music and madness, of spirits and symphonies, and of a man who dared to challenge the Wendigo, only to lose himself in the process.

Editor’s Note:

🚨 The Steamboat Dispatch advises against any further attempts to commune with the spirits of Chateaugay Lake, particularly those of a musical nature. The consequences of such endeavors are unpredictable at best, and at worst, could lead to a fate far worse than mere madness. We strongly urge our readers to leave the Wendigo in peace, and to enjoy the beauty of Chateaugay Lake from a safe and respectful distance.

What mysteries of Chateaugay Lake haunt you?