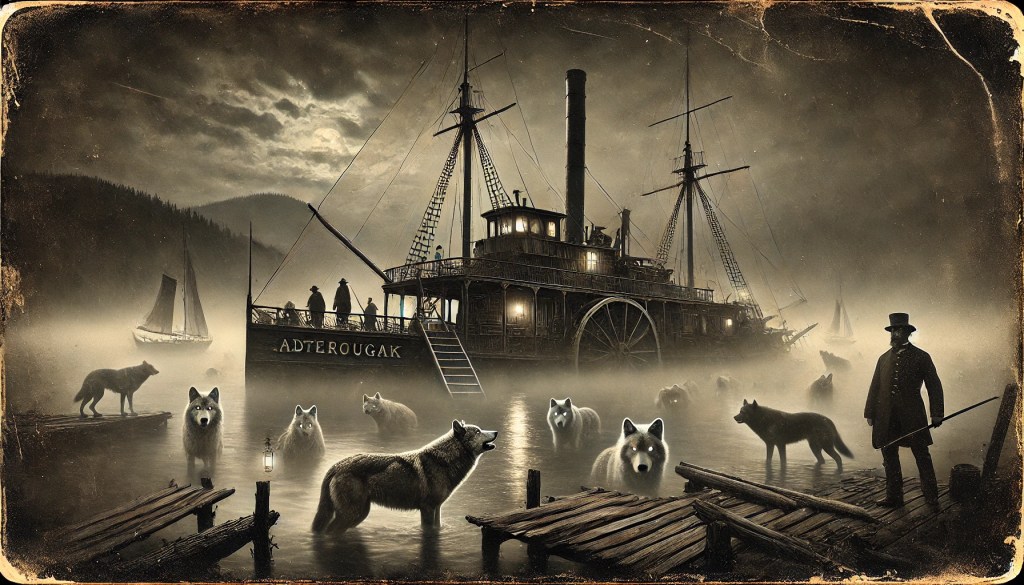

The Wolves of Chateaugay: A Steamboat Tale

By Thaddeus W. Moonhowl, Jr.

Rt. 2, Chateaugay, N.Y. 12920

Well, now, I reckon that when people start talkin’ about the howls on Chateaugay Lake, they’ve got it all wrong. Not that I’m one to dispute a man’s beliefs—after all, if you don’t trust what the elders say, what’s left for a man like me to do but pack up and wander off into the endless labyrinth of civilization, strayin’ too far from the campfire where the real truths lie?

Still, there’s somethin’ about those howls, you see—something strange and deep like the wood smoke that rises from the old cabins in the hollows, what can make a man stop and scratch his head, especially when he hears ‘em echoin’ back from the edge of Lyon Mountain, where the trees seem to whisper secrets about old times and darker things. My grandfather used to tell me tales about a night in 1879—about how he heard one such howl that cut the stillness of the woods. At the time, I thought it was just another of his tall tales, but well… now, I’m not so sure. What I know for certain is that it all started with the Adirondack and a crew of pirates who smuggled more than just contraband.

They weren’t your usual pirates—no cutlasses or eyepatches, just rugged local men, calloused from the steady beat of work and whiskey. Led by a wild-eyed fellow named Silas “Red” O’Hara, the crew turned our dear Chateaugay Lake into their own lawless kingdom. No one could stop ‘em, ‘cause they didn’t just deal in whiskey or fine silks—they dealt in wolves.

Now, you might wonder, “What’s a wolf doin’ on a steamboat?” Well, let me tell you, that’s where it gets real weird. You see, Red had himself a deal with traders up north, where the wolves still roamed the high hills of the Adirondacks. Timber wolves, mighty beasts, wild and free—what some folks hereabouts might call amitsuskwa, the spirit guardians of the deep woods. I reckon they were a lot like Red and his men—outlaws to the world, but somethin’ to be feared and revered all the same.

The trick was smuggling these wolves back into our corner of the world. After all, they’d been hunted to near extinction by bounty hunters looking for pelts. But Red, with his big ideas and bigger grins, thought he could bring ‘em back, make ‘em re-wild the place. Now, how he thought he’d get away with this in a place like Chateaugay Lake, where the lawmen like Sheriff Tuttle kept a watchful eye on everything—well, that’s beyond me. But there’s no doubt about it: he had the gumption for it.

They used the Adirondack, an old steamboat that once ferried folks to Chateaugay Lake View House. Below deck, instead of the luxurious cabins, Red had his men build pens—crude, tight pens where the wolves could be smuggled across the lake. The wolves didn’t take kindly to the whole idea of being crammed into cages, but Red knew how to handle things like that—he always had a way of getting what he wanted, even if he had to make the world turn in ways that didn’t quite feel natural.

One moonless night, the Adirondack set off from Indian Point. Now, my grandfather swore he was fishing from the shore, just sittin’ there with his lantern, when that old boat passed by—quiet as death itself. He said he heard the howls from below deck, wild and desperate, mixed with the eerie cry of a loon. He swore the whole night felt wrong, like the lake itself was howling back at the wolves.

But not everyone was so easy with Red’s scheme. The farmers along the lake, they were a practical bunch—wolves weren’t something you just let wander around, not when they’d tear up your livestock. And Sheriff Tuttle, well, he was a man of action—he once swore to send that Adirondack to the bottom of the lake, but that story never got to play out.

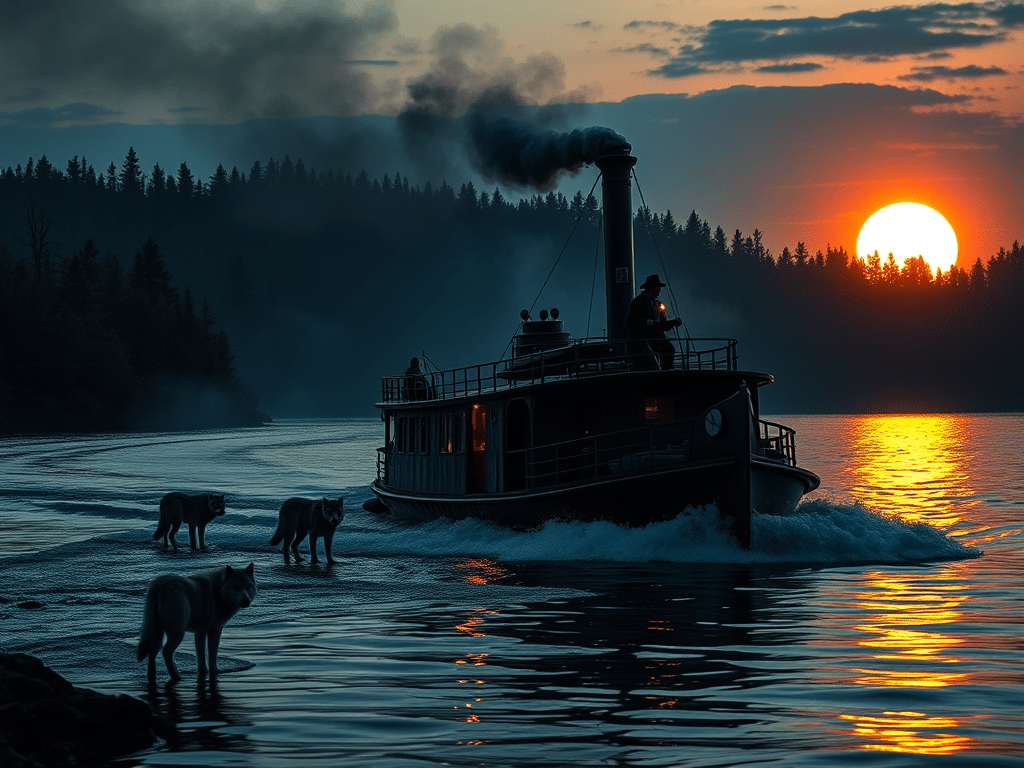

It was in the fall of 1879 that things really got wild. A storm—one of those big, howling storms that only the Adirondacks can cook up—swept across the lake. The Adirondack was halfway across, carrying the wolves in those tight pens below. They fought the storm, and Red, being the hard-headed son of a gun he was, stood at the wheel barking orders. The crew worked ‘round the clock, lanterns swinging, their faces lit by brief flashes of lightning. Below deck, the wolves howled, their cries lost in the wind.

When the storm passed, the boat limped into a sheltered cove near Sunset Inn. The crew, soaked and shaken, could barely stand. But Red, the fool, was grinning like he’d just won the lottery. “We’re still here,” he said. “And so are they.”

The Adirondack and its crew eventually faded away, like some half-forgotten ghost, but the wolves remained. The timber wolves—once nearly wiped out—started to return in small numbers, their mournful howls drifting through the trees again. A local legend was born.

These days, when I’m walkin’ the shores of Chateaugay Lake, I sometimes hear the faintest of howls, carried on the wind. It ain’t often, but when it happens, I think about those days. About Red, about the wolves, and about what it means when a man takes things into his own hands—even if those hands are bound by the ghosts of the past.

And when the moon rises over Lyon Mountain, its silver light reflected in the dark waters, I sometimes imagine that old Adirondack steamin’ through the mist, its whistle minglin’ with the wolves’ song. And, for just a moment, it feels like a part of me belongs there, with them.

What mysteries of Chateaugay Lake haunt you?