Architect Frank Morrison’s architectural madness continues to echo through Chateaugay Lake’s landscape. His floating city plans defy reason, bending perception and reality. Could these designs be a key to unlocking humanity’s hidden future—or its doom?

The Steamboat Dispatch

Special Edition

Chateaugay Lake, February 3, 1925

The Architectural Enigma of Frank “The Architect” Morrison: An Inquiry into Subterranean Ambitions and the Lake’s Unseen Tides

By Anson Wilde, Investigative Correspondent

“There are secret rivers that do not exist on any map.” — Frank Morrison, on the eve of his disappearance.

There are moments in history when the convergence of genius and madness takes root so deeply that the very soil beneath it begins to warp and pulse. So it was with Frank “The Architect” Morrison, whose remarkable creations—bridgeways that spiraled into clouds and homes built within mountains—left a mark upon the world, but not without consequences. His sudden disappearance in 1917—vanishing without a trace, with not even a whisper from his trusted foremen (whose connection to local powerbrokers remain, as of yet, uninvestigated)—has ignited a fire of whispers that still burns quietly beneath the surface of Chateaugay Lake.

Morrison, the reclusive genius, moved with an uncanny affinity for the region. Though his name is now synonymous with architectural wonder, it is only here, on the shores of Chateaugay Lake, that his true legacy may yet reveal itself, buried like some ancient relic of cosmic design.

Chateaugay, with its timeless tides and eerie undercurrents, has long been rumored to harbor hidden pathways that may not be strictly of the physical realm. In this way, Morrison’s work seems oddly prophetic in its connection to the mysteries of the lake. Perhaps this was his true aim—not just to design structures of beauty and mechanical intricacy, but to carve corridors in space and time. It is whispered by locals that Morrison did not merely build; he bent reality itself.

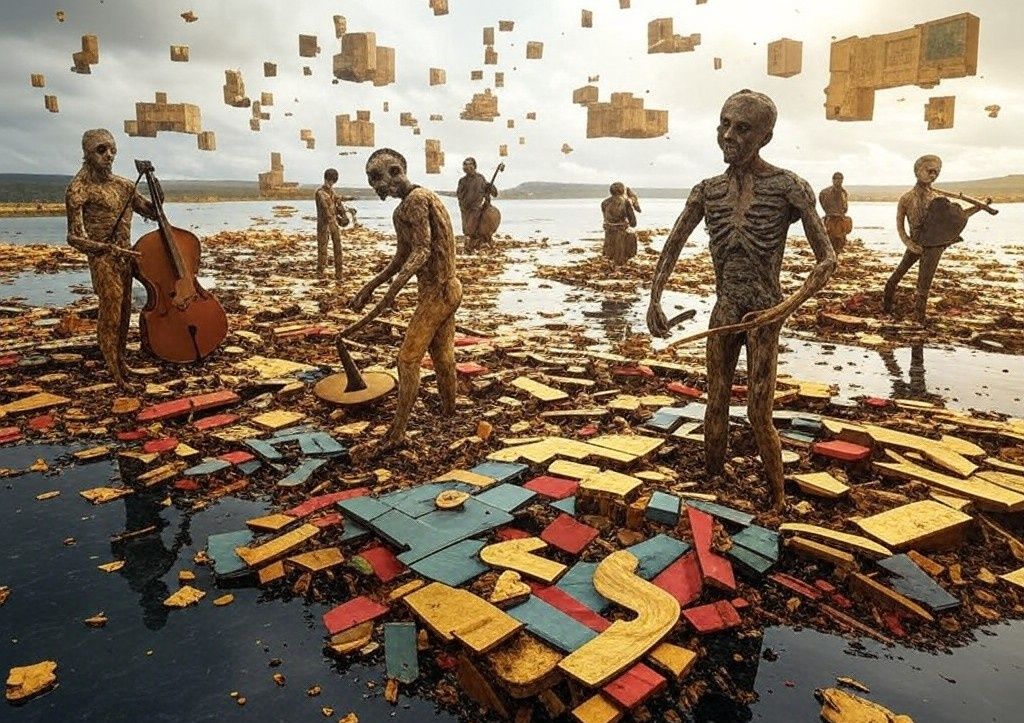

Among his eccentric circles—where artists, musicians, and arcane philosophers gathered at late-night “design sessions”—there arose talk of a “floating city.” The blueprint for this unearthly metropolis, rumored to have been sketched in the dead of night with the aid of certain artists and musicians who had long since stopped attending the formal “sessions,” is believed to have been lost after Morrison’s sudden departure. However, a fragment surfaced in 1917—stashed secretly among the forgotten papers of his former associate, the notorious Albert Drexler. The plan, as it were, showed an intricate city suspended not upon land, but upon the shifting currents of space and time itself—anchored by the mysteries of the deep. But the most curious detail? A musical instrument unlike any seen before: an unearthly device that was said to alter perception and reality—transforming sound into tangible matter.

The connection to Chateaugay Lake is undeniable, for it was here that Morrison’s obsession with invisible structures began to take form. It was not uncommon for Morrison to take solitary walks along the lake’s edge, where he would mutter to himself about “acoustic vectors” and “constructs beyond the perceivable.” His designs—originally dismissed by critics as the fleeting fancies of a man teetering on the precipice of madness—took on a new meaning after his disappearance.

Locals, particularly old timers from Bellmont and Indian Point, recount strange tales of Morrison walking along the lake’s shores, particularly near the Narrows and Ralph’s, seemingly engaged in quiet conversations with figures unseen. Some believe he was in contact with ancient forces that the lake concealed—beings that exist not entirely in this world but whose whispers reach through the cracks in time. Perhaps Morrison’s grand city was not a place of physical stone and steel but an interdimensional construct, a city made of sound and light and space, waiting to emerge from the hidden folds of Chateaugay Lake.

Morrison’s final design—a floating city built not upon Earth’s surface but on the very borders of perception—began to take shape in the minds of those who had known him. A city that was as much a psychological construct as it was a physical one. And some suspect, with no small degree of dread, that it is more than a mere blueprint.

This brings us to the most unsettling piece of evidence, one whispered in hushed tones by those who still dare to remember Morrison’s final days. According to the aforementioned blueprint—now partly fragmented by time and the efforts of those who seek to suppress its implications—the “floating city” is not a place at all. It is a state of mind, an elusive concept that shifts and alters with each new observer. Buildings in the design do not possess static forms but change, as if reflecting the inner turmoil of the beholder. It is as though Morrison’s final act was not the creation of a city at all, but the crafting of an entire reality—one that can no longer be undone.

But the true horror lies not in the disappearing lines of the blueprint itself, but in the chilling reports that have begun to surface from the residents of Chateaugay Lake. On quiet, fog-draped nights, those who wander near the water—some with the most curious, well-tuned instruments in hand—speak of seeing the remnants of Morrison’s designs in the depths, where shifting shadows play tricks upon the eyes. More disturbingly, certain voices can be heard in the stillness, faint echoes of the same disjointed melodies he once composed for his floating city.

In this surreal twist of fate, one is left to ponder whether Morrison’s final act of genius was indeed to create a city that can never be built, a place that lies not in the physical world but within the infinite, shifting expanse of the mind itself. The question remains: is Chateaugay Lake a mere reflection of that city, or is the lake itself the final structure—a lake whose waters may one day rise to reveal the lost city, where the boundary between the known and the unknown, between the living and the lost, ceases to exist?

For now, we are left with only these fractured blueprints, scattered notes, and the eerie refrain of distant music carried by the wind—a reminder that sometimes, the true architecture of reality lies in the spaces between the notes, in the shadows cast upon the waters.

The mystery of Frank “The Architect” Morrison may never be solved. But in the watery depths of Chateaugay Lake, it is certain that his legacy continues to haunt, to reshape, and to beckon the curious toward an unimaginable future. Or perhaps, a past that never was.

— J.P. Bernet, Editor

What mysteries of Chateaugay Lake haunt you?