Deep in the Adirondack wilderness, where civilization’s grip loosens like fingers from a drownin’ man’s throat, lies a body of water that has witnessed horrors older than human memory. This is the story of Chateaugay Lake—a place the indigenous once called “Chetegewet,” the “Place Where the Sky Hums,” where Dutch spies uncovered forbidden secrets, where the Beaver Wars unleashed forces beyond human comprehension, and where the very trees lean inward, listenin’ to conversations not meant for mortal ears.

The Dutch Curse: Van den Bogaert’s Fatal Discovery

Wal now, folks around here say the darkness in Shatagee Woods comes from some old trapper’s curse or a logger’s yarn. But I tell ye, this particular evil got its start long before any white man set foot in these woods. Back in the icy winter of 1634, a Dutch barber-surgeon named Harmen van den Bogaert came pokin’ through these parts, and he found somethin’ he ought not have.

Van den Bogaert warn’t here to admire the pines or hunt game, no sir. He was sent by the Dutch West India Company to map fur routes and spy on the native nations. In those frozen swamps and hemlock stands, he stumbled on a secret that near drove him mad. See, the local Algonquian people had knowledge of this land that ran bone-deep—stranger than anythin’ a city-bred man could grasp. That Dutchman scribbled in his journal about warriors who could see things before they happened. Fighters movin’ like shadows, always one step ahead of their foes. He realized these men were dosin’ themselves with a peculiar brew: a mix of white-pine sap, swamp moss, and glands from the fat black frogs that live in the bogs and springs behind the headwaters of Upper Chateaugay Lake. Drink it under a new moon, and ye could open yer eyes to the other side of the air. That’s my phrasing, mind ye—van den Bogaert wrote of a “shimmerin’ sight” and hearing “voices in the sky.” Whatever it did, it let a warrior sense an ambush before it sprang and hear footsteps in the dark clear as day.

How could he tell his masters that the people he aimed to conquer had an edge straight out of a nightmare? He never got the chance. Word is, van den Bogaert fled Albany under a scandalous cloud of fear. He vanished back into the wilderness, never to return. Some insist his bones lie sunk in a swamp up Painter Mountain way, clutchin’ the terrible secret he discovered. If ye wander near that bog on a winter night, ye might hear a faint hummin’—maybe it’s him, still tryin’ to warn whoever will listen.

The Frog-Eaters: War Magic in the Woods

When the Beaver Wars raged through these mountains, fightin’ warn’t just muskets and tomahawks. Nosirree, it had a hunger to it that went beyond the ordinary. The Algonquin defenders of this region—Abenaki, Mohican, Lenape and their kin—were fightin’ for their very lives against Iroquois conquest and European guns. They turned to the old ways and wild wisdom of Shatagee Woods, and that included uncanny frog-brew magic.

I’ve heard folks chuckle at the notion of frog juice grantin’ mystic powers, but listen here: those elders knew a thing or two modern science is only just figgerin’ out. That concoction wasn’t mere superstition; it was forest pharmacology. Braves would drink it, then sit still around their fires, eyes rolled back white, mumblin’ in tongues older than these hills. After a time they’d rise, guided by visions only they could see, and slip off into the night.

Imagine ye’re a Haudenosaunee warrior creepin’ through the pines, thinkin’ ye have the drop on an Algonquin scout. All of a sudden, an arrow whistles out of nowhere and finds its mark before ye even step into the clearing! Yep, them Algonquins already knew ye were comin’. They called that heightened state the shimmerin’ time, when past and future ran together like spring meltwater.

It was the land itself lendin’ power to those willing to partake of its strange, livin’ medicine. ‘Course, every power has its price. The stories say those who took the frog-brew too often started hearin’ voices even when they warn’t under its spell. A man might catch a low call from the empty trees, or see a flicker of someone not there at the corner of his eye. The line between our world and whatever lies beyond grew thin as a deer hair. And linger in that in-between too long, ye can bet somethin’ else will start lookin’ back at ye from the dark.

The Lenape Trail and the Owlyout Mystery

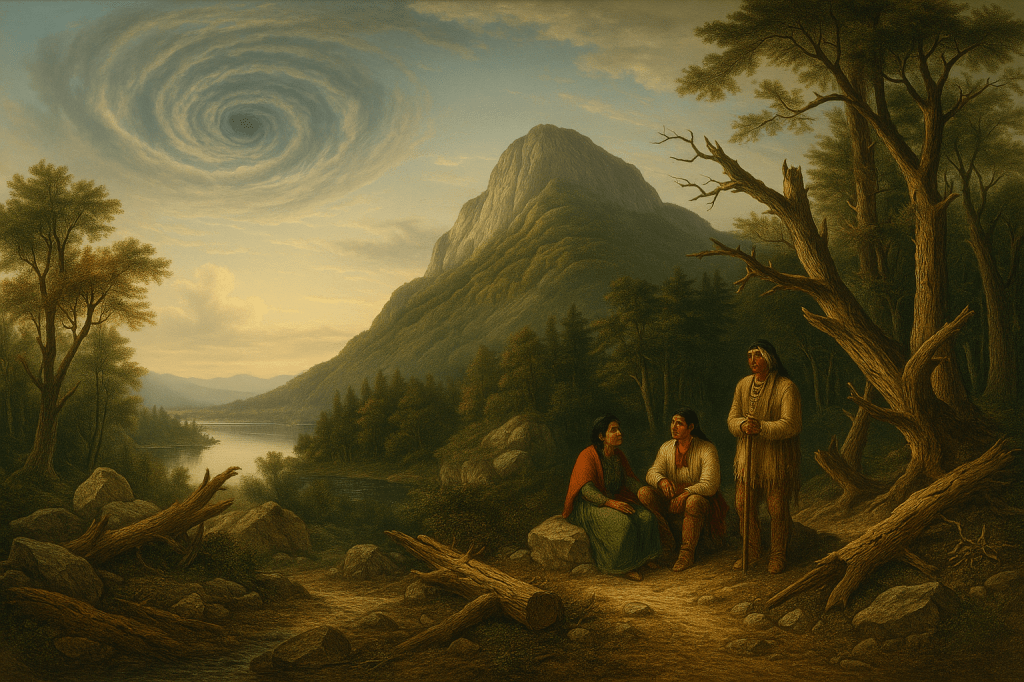

Years after the gunfire died down, a small band of Lenape from downstate kept up an annual pilgrimage to this lake. Though their homeland was in Delaware County far to the south, these folks never forgot the old routes north. Every summer into the mid-1800s, they’d trek through the Mohawk Valley and beyond, all the way to a big sand bar on the lower end of Upper Chateaugay Lake where they camped.

There’s a tale from just after the War of 1812 about a white settler who accompanied the Lenape one summer. He followed their trail to that sandy beach camp. While there, he fished a little trout stream so much like one on his farm back home—called Owlyout, meaning “great trout breeder”—that he gave this northern brook the same name. Ever since, folks have called that stream the Owlyout.

Arrowheads and fire-cracked stones still turn up on that beach, silent testimony to those yearly gatherings. Now, they may have been friendly visitors, but mark my words: they weren’t coming all that way just for the fishin’. I suspect they came to honor something their elders knew lurked here, to keep a watchful eye on a power in these woods. Each summer, their campfire songs and offerings were like renewing a truce between their people and the unseen. And when those visits finally ceased, it was as if the watchmen had abandoned their post—and something in the Shatagee wilderness was left unguarded.

The Gitaskog: Serpent of the Lake

Not all the strange things in these parts walk on two legs. Both Abenaki and Mohawk lore tell of a giant water-dweller in Chateaugay’s depths—some call it Gitaskog, others just the Great Snake. So long as the native rituals continued, the Gitaskog stayed deep and dormant, slumberin’ under the spell of old songs. But after those pilgrimages stopped, folks around the lake began glimpsin’ something mighty peculiar in the moonlit waters.

The first big sighting on record came in 1890, when a local paper reported a “sea serpent” in the Upper Lake. A massive, snake-like creature—dark and slick—was seen undulating through Bellows Bay and near the Narrows. One guide swore it matched the beast folks had been spottin’ over in Lake Champlain (where they nickname their serpent Champ). The skeptics scoffed, since Upper Chateaugay is landlocked. But old Nat Collins, that veteran guide, insisted there were hidden channels and flooded caves underground big enough for a leviathan to slip through. Nat even claimed he’d found a cavern near the Upper Lake so vast it “far exceeded Mammoth Cave in Kentucky”. If anyone could find a secret waterway, it’d be Nat, nosin’ around in flooded caves like a blind crawfish.

Whenever that critter did surface, the forest went as still as a church. One calm summer evenin’, a great dark form slid under my Uncle’s rowboat out on Devil’s Channel. He didn’t wait to see more—paddled for shore white as a birch. He said it felt like an ancient gaze fixed on him from beneath that black water, cold and curious, weighin’ him up like a fisherman eyein’ a catch.

The Wendigo’s Shadow

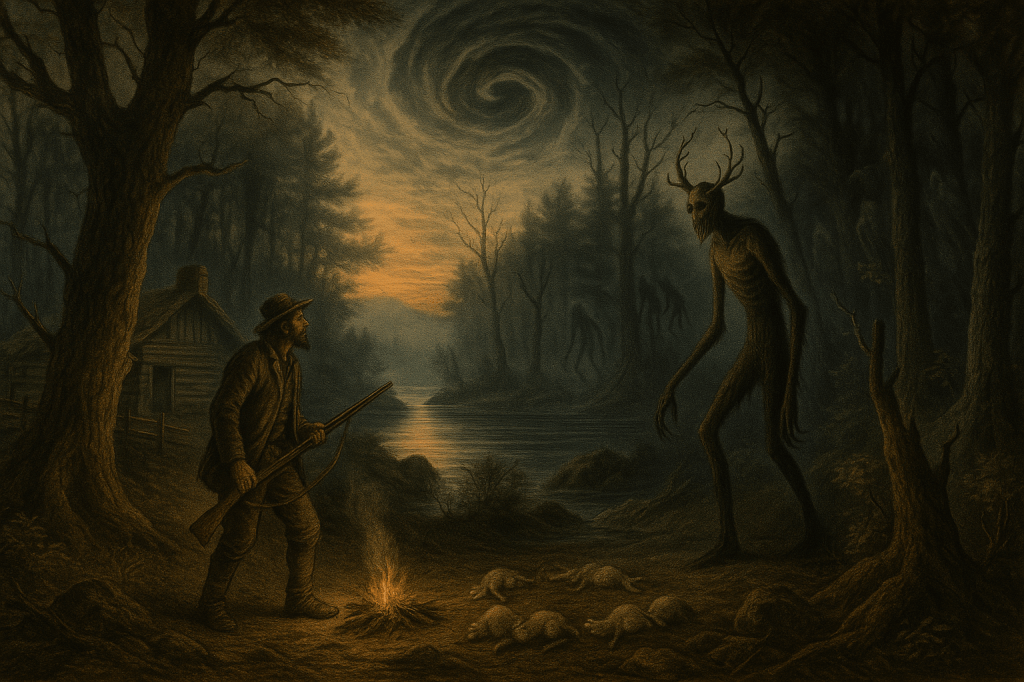

If the lake has its monster, the woods have their own boogeyman: the Wendigo of Shatagee. Most Wendigo tales hail from farther north and west—Ojibwe and Cree country—speakin’ of a winter cannibal spirit. Our version has a twist, likely thanks to those war medicines and traumas seeped into the soil. Up here, they say the Wendigo feeds not just on flesh, but on fear and sanity.

It often starts with a lone trapper or hunter spendin’ too many nights in the deep woods around the South Inlet, maybe near old Nat Collins’ cabin site on Baker Point. The forest there goes quiet as a grave. Then the poor soul notices things ain’t right. Trees seem to shift at the corner of his vision. Strange shapes peer from behind trunks, then vanish when looked at straight. He might hear his own name in the pine needles—only there’s no wind to carry any voice. That ancient name Chetegewet, Place Where the Sky Hums, starts to make an eerie kind of sense as a faint vibration fills the air.

They say the Wendigo of Shatagee Woods is patient. It likes to play with its prey. A hunter might wake up to find a ring of dead hares laid around his campfire, gentle as little dolls, not a mark on ’em. Each impossible sign, each unsettling omen, gnaws at a man’s mind. By the time the Wendigo finally shows itself—maybe as an impossibly tall silhouette at dusk, half-hidden behind a stump—he’s so shaken he can barely stand, let alone run.

Some say that during those old wars, a few braves who overused the frog-brew lost themselves and became something like Wendigos. They gave so much of their mind to the voices beyond that an inhuman hunger filled the void. Whether that’s true or just a yarn to scare youngsters, I can’t say. But I’ve seen enough strange things out there to give the tale a fair bit of credit.

Lost Mine, Lost Guardians

Secrets breed more secrets in these hills. After the Lenape quit coming and the last native guides were gone, plenty of old knowledge went to ground. One legend that refuses to die is the tale of a lost lead mine on Lyon Mountain, that hulking peak just east of the lake. In the mid-1800s, Nathaniel “Nat” Collins (the same guide who spoke of hidden caves) nearly found that mine, and folks here still talk about what happened.

Nat was fishin’ up the South Inlet one morning when he stumbled on three Indian travelers camped quiet by the shore. They weren’t from any local tribe. The daughter spoke fine English and said they were on a long hunting trip. Nat offered the warmth of his cabin nearby, and the family lingered close for a good two weeks. In time, the girl let slip that her father—a chief from far off—had come to gather lead ore from a secret vein in Lyon Mountain, used for their bullets.

Naturally, Nat asked if she’d show him this miraculous mine. She just smiled and gave him a playful riddle instead of plain directions. She spoke of a pointed rock by the brook, a fallen spruce with water gushing through, an old hemlock stump with pegs in it—all leading toward the lode. But she never revealed the final turn. When Nat pressed her, she laughed, “If I told ye that, my father would shoot me.”

Well, ye can imagine Nat tried to trail them as soon as they slipped away. But those folks were too crafty. They doubled back and hid their tracks, and he lost ’em in no time. Nat combed every brook and ridge he could, but never found so much as a nugget of that lead.

A while later, an old timer named Mose Sangamo over by Chazy Lake claimed he’d found a cave in Lyon Mountain lined with veins of lead and signs of a recent fire. But when Mose returned with friends, there was nothin’ to be found—as if the mountain had swallowed the whole works overnight. Mose figured those Indians wiped away his trail markers and led him off the scent.

Even now, treasure hunters scour Lyon Mountain for that Lenape lode. They turn up a spent bullet mold here, a heap of charcoal there—signs someone smelted lead in those woods—but the mine itself stays hidden. It’s as if the mountain closed its jaws around it. Some say the Lenape collapsed the entrance when they left, keepin’ it out of white men’s hands. Others reckon something else in that mountain wanted its den sealed. Given the spook lights and ghostly figures folks sometimes report on Lyon Mountain, maybe that mine was more than just a source of metal—maybe it was a doorway to something the Lenape knew must never be let loose.

Modern Murmurs in the Pines

Ye might be thinkin’ this is all just old lore—campfire tales. But I assure ye, the strange legacy of Chateaugay Lake is alive and well. Ask any old-timer or ranger in these parts, and you’ll get an uneasy tale.

Fishermen still haul up lake trout bearing scars like unknown symbols, as if some ancient language was etched in their scales. Electronics misbehave near certain coves—GPS units die, compasses spin wild. Just last year, two seasoned hikers vanished on a clear afternoon up on Lyon Mountain. The searchers found their boot prints in a patch of mud, then nothing—like they’d been plucked into the sky. Not a trace of those boys has turned up since.

And then there’s the sound. Campers talk about a low hum that rises from the woods at night, so faint ye’d swear it’s your own heartbeat—until it stops, and a shrill wail follows that makes your blood run cold. One local woman swore she had a page from van den Bogaert’s journal describing that hum as the speech of spirits. After she died, that page vanished into some government archive, like the authorities didn’t want anyone seein’ it. But we know better.

We who live in these mountains—who wake to the loon’s cry at dawn and fall asleep to the owl’s hoot at midnight—we know Chateaugay Lake ain’t given up all its secrets. We see odd footprints appear in fresh snow, circlin’ our cabins with no beginning or end. We notice how the woods can go from lively to dead silent in a heartbeat, and when it does, we just exchange a glance and remember all those old stories.

The Lake’s Dark Inheritance

For all its clear waters and tranquil scenery, Chateaugay Lake carries an inheritance as dark and deep as its boggy hollows. The clashes of long ago—between native and settler, and between mortal folk and the unknown—left scars on this land that still ache. The native peoples knew one truth: some places in this world are alive with a power that demands respect. Those who walked away from Chetegewet tried to leave guardians and warnings for those who would come after. But time and colonization made folks forget those old pacts.

The result is a kind of breach, like a dam cracked under pressure. We might blame bad luck when someone vanishes, but some suspect the balance tipped when the last elder left and the rituals ceased—when the woods were left unwatched. Now the Gitaskog stirs whenever it pleases, the Wendigo’s presence seeps into cabins in the dead of winter, and even on calm afternoons the sky sometimes hums its uneasy tune over the lake.

Yet all is not lost. A new generation of storytellers and guides keeps these tales alive, hoping to mend what was torn. Maybe by retellin’ this chronicle—acknowledgin’ the ancient wars and the horrors that still lurk beneath the hemlocks—we pay homage to those who kept watch here long before us. Perhaps we even grant the restless spirits (Dutch adventurers, Lenape guardians, or whatever else watches from the dark) the respect they’re due.

So if ye ever find yerself up on Chateaugay Lake, driftin’ in a canoe as dusk turns the peaks purple, listen close. Ye might catch a low murmur among the pines. It could be the wind… or it could be an old voice from the Shatagee Woods remindin’ us that some places remember everything. And if ye’re wise, ye’ll tip yer cap to the silence and offer a polite hello. After all, in a land this old and strange, it costs nothin’ to show a little respect—and it might just save yer skin one dark night when the woods come alive with the secrets of the past.

Johqu Bogart, 30 June 2025, Lower Chateaugay Lake

What mysteries of Chateaugay Lake haunt you?