Advisory: Story includes intense scenes of geological horror, missing persons, cranial unease, and the psychic implications of mining a sentient ore vein. Historical accuracy may deepen reader discomfort. Proceed with caution.

THE LODE IN THE LAKEBONE

A Chateaugay Lake Tale

Transcribed from the marginalia of the Bellows Ledger, recovered in 1987 from beneath the forge stone at The Narrows.

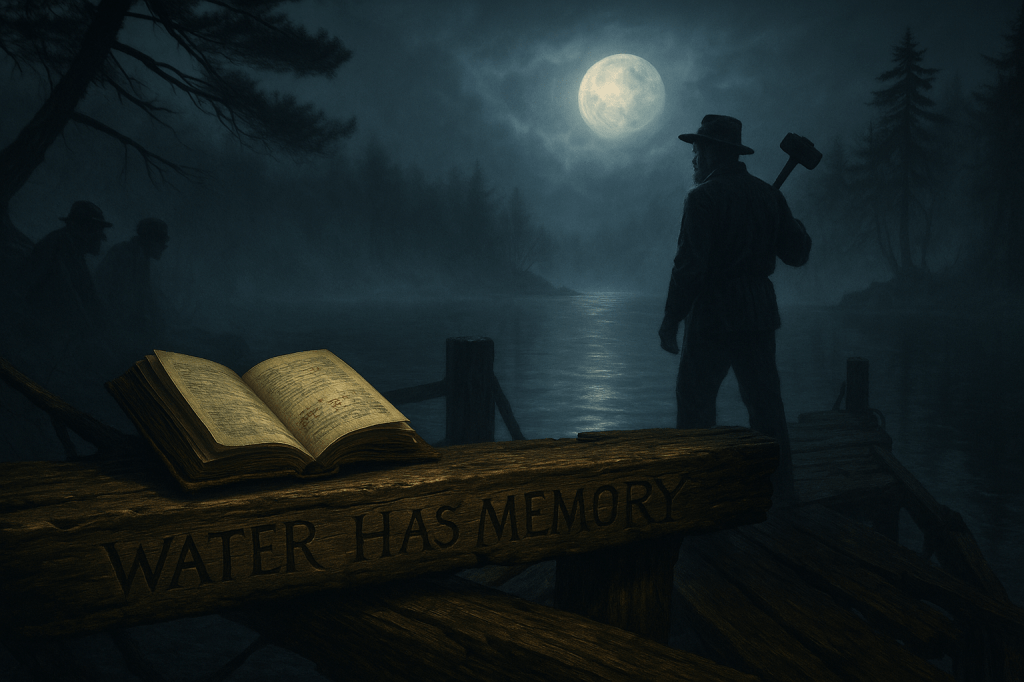

“Water has memory,” the old men muttered.

“No,” replied the blacksmith, “it has intent.”

—Scratched into the beam above the Narrows Ferry Dock, 1891.

The Ledger and the Last Bellows

It began with a ledger—its pages damp, but the ink intact as if protected by some breathless guardian. Discovered by accident, of course—nothing true at Chateaugay is ever sought, only stumbled upon when the moon leans wrong and the fog bleeds silver.

Cassius Bellows, youngest son of Stephen, long thought vanished in the fall of 1888, had etched his final entries in a trembling script, half-factual, half-confessional. Most was account-keeping: butter tub orders, charcoal weight tallies, ore volumes from the failed Upper Diggings. But toward the back—pasted between two pages as though sewn shut by a nervous wife’s hand—was a loose sheet written in red ink or blood or both.

That sheet tells the true story of The Lode in the Lakebone. And I warn you, reader: once you read it, Chateaugay is never just a lake again.

The Bending of the Mine

In 1876, they found a vein—no, a limb—of lead ore unlike any seen before. Not the dull gray smear of Galena, but a dark-gloss vein, jointed like cartilage and embedded with nodules that rang like bone when tapped. It ran under the Narrows, from the far side of Popple Point to beneath the old smelter road.

Locals called it “The Lakebone.”

Mose Sangamore—trapper, drunkard, and part-time guide—swore he’d seen the ore twitch when the moon was at perigee. “Not the vein,” he’d croak, “but the bone. Like somethin’s tryin’ to roll over, down there.”

He wasn’t believed. But they paid him in muskrat pelts and red-eye liquor to keep mining it. And dig they did—until the strike went too deep, beyond where the rock held memory. Where the air became humid with a scent no one could name, though some likened it to old spoons, blood, and musty church pews.

They struck something. Not ore.

Something… hollow.

The Widow’s Seining Net

The first sign came to Marjorie Pope, who set out one morning to seine minnows near the rusted Gadway Ferry pilings. She dredged up no fish, but instead a human head!—hair still attached, though greened with algae. Not an old one, either. The blood had not yet gone fully black.

The head was later confirmed as that of Professor A.B. Hiram, a geologist from Albany who’d been sent to map the Forge’s ore composition.

He had vanished six weeks prior after muttering about “stratigraphic anomalies” and something he called temporal inversions in sedimentary tissue. His last known act was posting a letter to someone named W. James in Cambridge, Massachusetts, regarding “the psychic permeability of lacustrine orebeds.”

No one knew what any of it meant.

But after his head was found, the lake grew quiet. The loons stopped calling. The ice never fully thawed that spring.

And at night… folks heard a clicking beneath their floorboards.

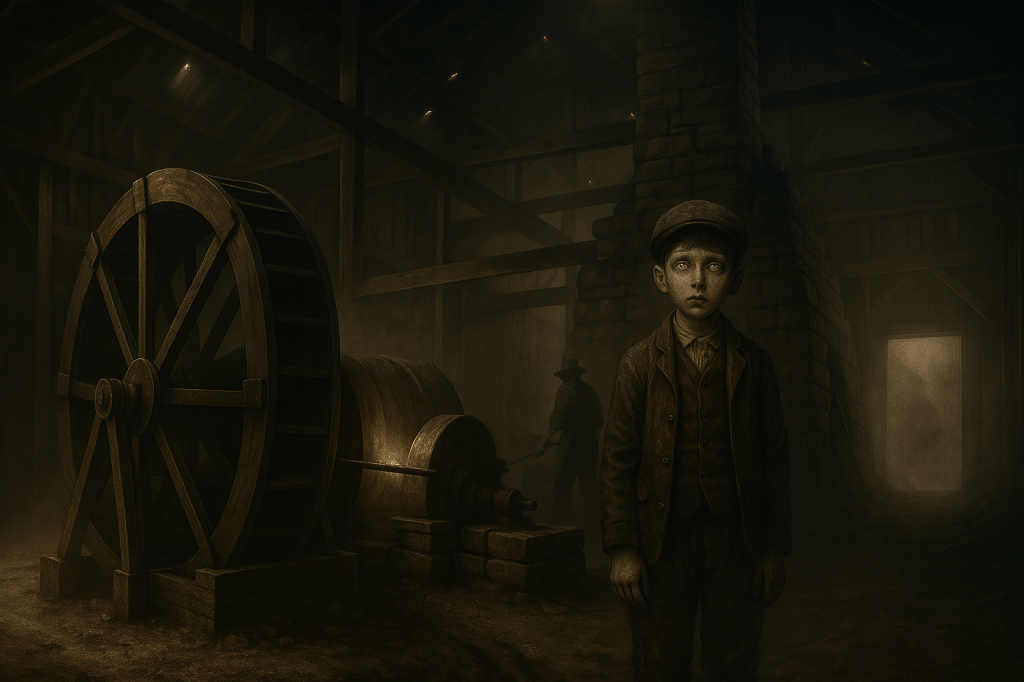

The Thirteenth Kiln

There were supposed to be twelve charcoal kilns above The Forge. Twelve. Every map said so. The tax records said so. The Bellows ledger said so.

Yet every now and then—especially in fog, or when the weather swung warm to cold in a snap—people counted thirteen.

That extra kiln was never in the same place twice.

Alonzo Bellows, age nine, wandered into it once chasing a stray dog named Pinto. When they found him two days later, his eyes had gone all milky and he spoke only in backwards French.

“Elle creuse… elle respire…”

(“She digs… she breathes…”)

His dog was never found. But two weeks later, the men dredging the lake for smuggler traps found Pinto’s collar, attached to something wrong—something that looked like cartilage encased in lead, with blood-vessels turned to rusting veins.

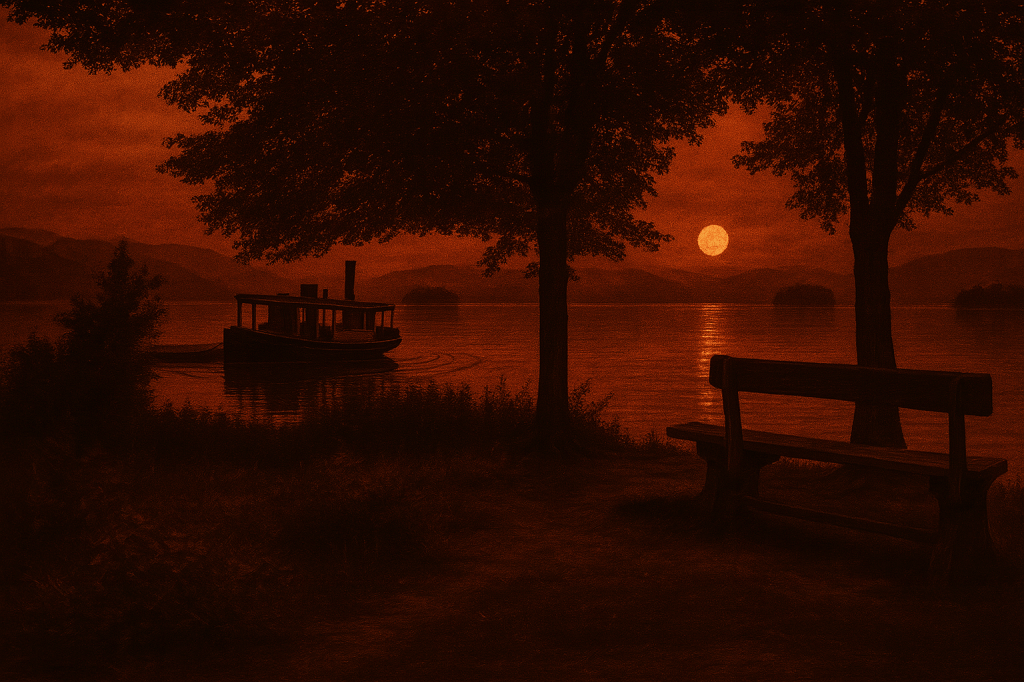

The Mouth at the Narrows

In July of 1888, Cassius wrote that he had “heard the mine groan.” That’s the word he used—groan—not crack, not shift. He claimed the tunnel collapsed not from pressure, but from inhalation. Like the mountain breathed inward.

From then on, people disappeared—mostly miners, a few teenagers, and once, horribly, a whole steamboat party. The Eunice Kirby, launched from the sandbar with twelve aboard, was never seen again. Only the stern paddle and one woman’s slipper were found—half-melted, fused with some grotesque vitreous slag, like it had been pressed into glass.

The mine was sealed. But the lake didn’t forget.

And when the Forge shut down in ‘93, the locals left. Not in anger or failure—but with quiet dread, like people who had seen the forest blink.

The Modern Excavation

In 1987, Alfie King’s nephew tried to rebuild the store cellar wall and unearthed the Bellows ledger in the process. That very night, the sandbar flooded without rain. Two to three feet deep, some say. Been that way ever since.

Pontoon boats swamped.

Fish turned belly-up, mouths gaping not in death, but in a kind of echo. Like they’d swallowed a scream they couldn’t digest.

And that old thirteenth kiln? A hunter swore he saw it again—up near Lyon Mountain’s shadow.

Inside it: bones. Not human. But shaped like the fused ribcage of something humanoid that had never walked upright. Black and glossy. As though coated in… lake mud and charcoal soot.

The Name Was Not French

They always assumed the name “Chateaugay” was French, some old family of noble knights or princesses or a ruined castle back in the homeland with a dank dungeon. But one line in Cassius’s red-ink page changed everything.

“The name is not French. It’s not even language. It’s the sound the Lode makes, in moonwater: Shataa-gayy. I have heard it speak. We are standing on a skull. We live upon a buried thought.”

You Are Hearing It Too

Listen tonight, if the frogs fall silent.

Stand at the Narrows. Wait until the wind shifts.

You’ll hear the water pull.

Like lungs under a floorboard.

And if you hear your own name—not spoken, but exhaled—do not answer.

The Lake remembers.

The Bone remembers.

And the thirteenth kiln is never where you left it.

Not anymore.

Not since the Bellows boy drew breath beneath it, and breathed back.

Filed under Restricted Regional Lore: CH-13-B (Lakebone Files). Do not distribute without glacial permit.

What mysteries of Chateaugay Lake haunt you?