Listen, flannel philosopher: frogs go quiet, air don’t move, and a hum like trumpet reeds comes creepin’—get back to camp. That scum-haired face ain’t here to trade blueberries, hey?

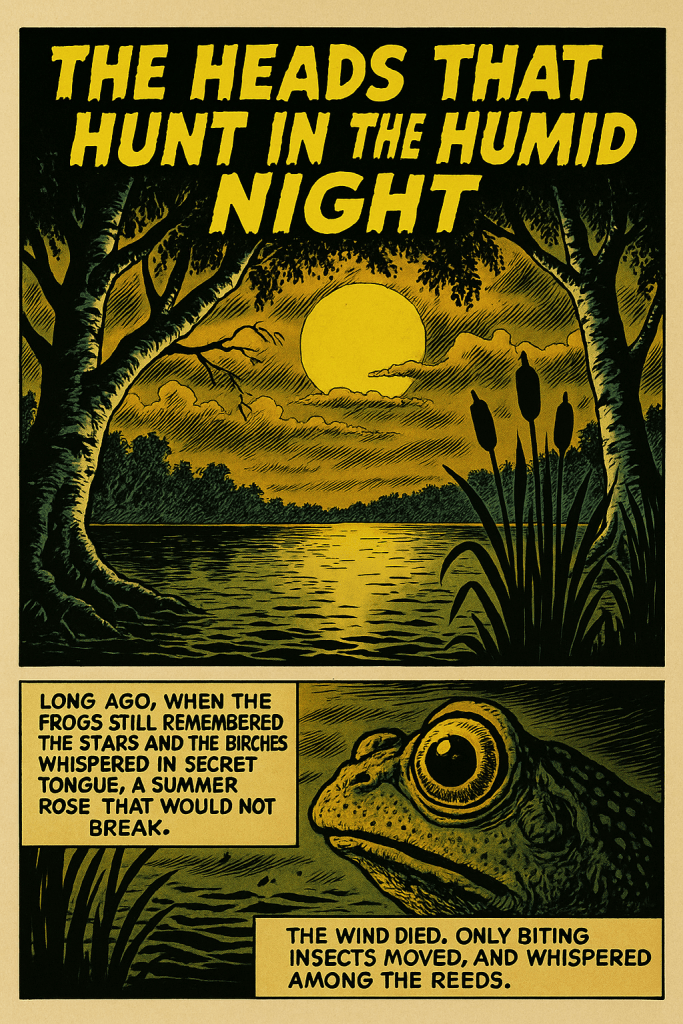

THE HEADS THAT HUNT IN THE HUMID NIGHT

(As told by an Elder of the Onondaga, gathered near Chateaugay Lake, July 1894. Collected by E. W. Laughingstone, Field Notes, Vol. III, p. 71.)

Long ago, when the frogs still remembered the stars and the old birch trees leaned together in secret speech, there came a summer that would not break. For seven turnings of the moon, the sun hung low and heavy above the Shatagee Woods, smothering the hills in a breathless, yellow haze. The wind lay dead; only the biting insects moved, and even they whispered warnings among the reeds.

In those nights—when even the owls held their tongues and the fish lurked deep in cool, stone-shadowed water—the People slept poorly, their dreams muddied and thick with dread. For each morning, before the pink sky bled over the big lake, there were new tracks in the black sand at the edge of the marsh—tracks round as bowls, gouged and pressed deep, yet bearing no mark of foot nor claw. Only the elders, wrapped in their blankets, knew what such signs foretold, and they were not eager to speak.

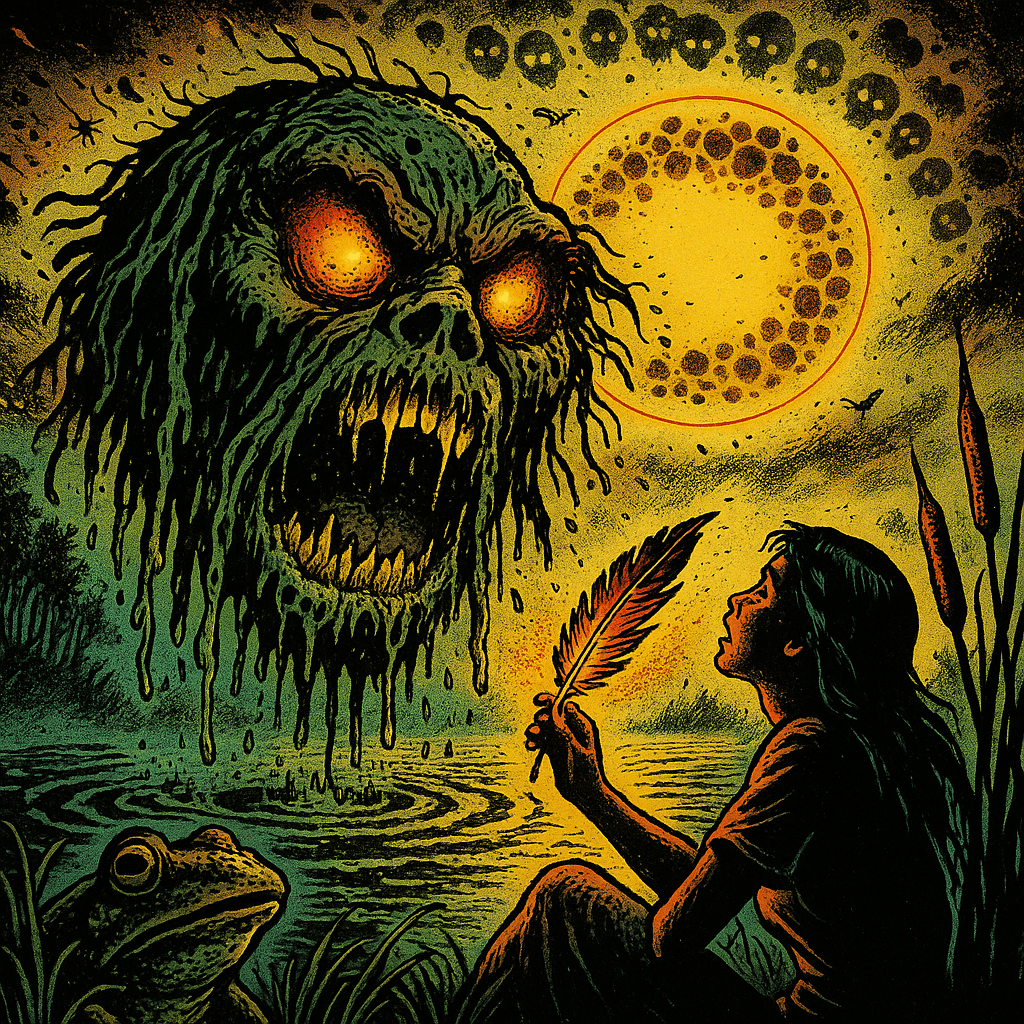

One night, when the moss still sweated from the day’s heat, a young woman called Otetiani—she who is prepared—sat alone beside the water, cooling her feet among the cattails. She was neither foolish nor brave, but something gnawed at her heart: her little brother had vanished that morning, his basket of berries spilled in a silent trail up the slope. The men had searched; only the frogs replied.

As the darkness thickened, she heard a humming, low and strange, not unlike the wind through hollow reeds, but it carried the taste of iron and old fire. She peered across the bay, and the trees bowed away from a form rising above the mud—no taller than a boulder, yet moving with a hunger older than the stone itself.

It was the Head: no body, only a face vast and wet with lake-scum, hair like water weeds trailing behind, and teeth glinting as if carved from fishbone. Its eyes burned with summer lightning. Where it passed, the air curdled, and the wild celery drooped.

Otetiani was rooted, as the pines are rooted. The Head’s voice scraped like dry willow:

“Give me what was promised, child of the quiet house. Give me the flesh that forgets to tremble, or I shall feast on your shadow.”

But Otetiani remembered the words of her grandmother, spoken during the long winter: When the Head comes, show it a circle; make it follow itself until it drowns in its own hunger.

So she cupped her hands and sang a song not of her own making—a song older than bread or fire, the turning-song of midsummer, which winds the moon and the eel together:

Circle the reed,

Circle the stone,

Find the hollow,

Go alone—

The Head, greedy and witless, began to chase the shape of her song, spinning round and round the marshy hollow. Its mouth gaped wider, its eyes flickered and dimmed, for the song’s path had no end. At last, overcome with longing and rage, it plunged its teeth into its own shadow on the water, and the mud swallowed it up with a sigh.

Otetiani wept, for though the Head had vanished, the air still prickled with dread, and her brother did not return.

Yet as dawn crept along the lake’s rim, she found, nestled in the cattails, a single feather stained red and black—a hawk’s plume, tied with a twist of river grass. Her grandmother, when she saw it, bowed her head and murmured:

“It is a sign. The boy walks with the ancestors now, swift as the hawk and unafraid of the Heads.”

In the days that followed, the heat broke. Rain came, and the frogs remembered to sing again. But the elders built a small fire each evening beside the reeds, and none drank from the marsh unless they circled their hands thrice above the water, drawing the old shape to ward away what hungers.

Even now, when July hangs breathless and the thunder waits just beyond the hills, the people remember Otetiani’s vigil. Children are told: do not stray into the heat-mist, do not answer voices that roll like stones across the water, and if you meet a Head—sing it a circle, lest it swallow your shadow, too.

And so, on humid nights, the reeds sway west not for wind, but to remember the turning-song, and the mud keeps its secrets until the next summer the air forgets to breathe.

(Editor’s Note: No further accounts of the Flying Heads were collected during that season, though the old women would sometimes leave bread or small beads among the reeds at sunset, “for the ones that circle, and for those who do not come home.”)

What mysteries of Chateaugay Lake haunt you?