Trigger Warning:

Historical Language & Ambiguous Portrayals — Old Settler Voice

Nicknames (e.g., “Mose Sangamore”), frontier judgments, and period terminology appear; portrayals reflect 19th-century Adirondack context and may not align with modern sensibilities.

A Night Alarm at the North End of Chazy Lake—Supposed Outrage—Found to be of a Different Nature.

(Letter to the Editor.)

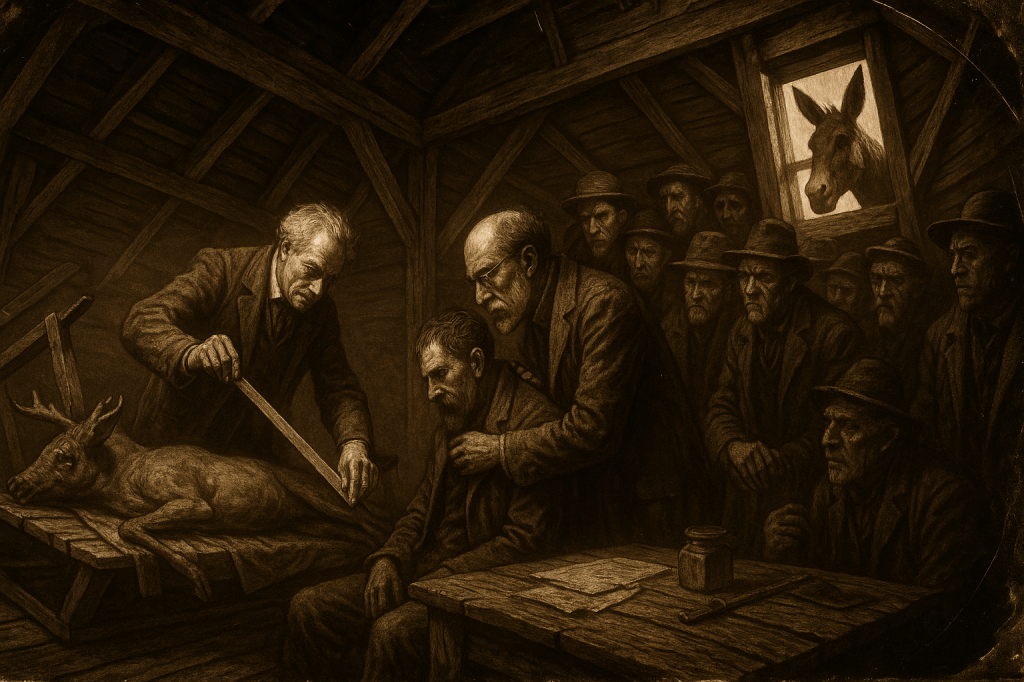

On the night of the 11th of this month, about ten o’clock, a cry was heard from the hardwood ravine north of Mr. Bell’s pasture at the head of Chazy Lake, which several persons from Bellmont, being then abroad upon small business of their own, took to be a woman’s scream, whereupon an alarm was given at once; a party was formed with lanterns, the constable was fetched, and, after proceeding by the tote-road to the cedar brake, they came upon one Moses St. Germain—commonly called Mose Sangamore—asleep with his back to a stump and a deer newly killed upon the sled, while his small donkey stood over him, ears forward, as if upon sentry; the supposed scream proving to be the animal’s bray reverberated along the gully and multiplied by the shaped banks of the stream. As to the man, he offered no resistance; as to the deer, he claimed it fairly, alleging a lawful day’s hunt and fatigue. The party, being uncertain of the law upon the precise hour and the method of taking, held him to await examination in the morning.

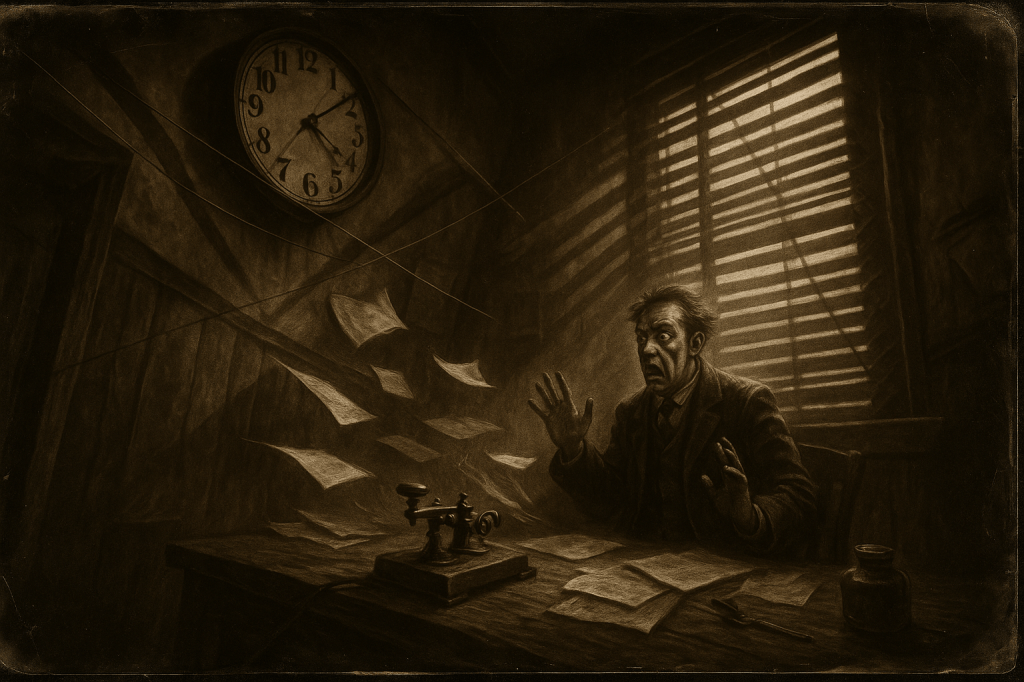

As several of the party state it, the cry had such force as to carry clear to the lake road. One insists the sound shook panes at Mr. Mead’s shed; another that the telegraph at the Forge ticked irregularly for several moments without a hand upon the key—an assertion less unlikely than it first appears, there being a wire from Chateaugay village to the Bellmont iron works in active service these past years.

Counter to these statements, Mr. St. Germain claims that he had laid down after dressing the deer and that the animal, being wary of dogs, brayed only once; on the contrary, two boys from the Chazy lakeshore aver to three distinct cries, not far apart. No other person is reported missing; no garments were found; no signs of struggle appeared beyond the ordinary trample of a drag and one lantern knocked into the moss.

The morning after, an examination was had over at the Forge lakeside storehouse before Justice Percy; the deer was produced, the sled measured, and the hour set down from the constable’s book. The physician—Dr. Johnson, lately attending many of the lake dwellers—reported no injuries to Mr. St. Germain beyond sap-blister and smoke-eye from his own fire. (The doctor is well known in that quarter from his former service to the village at the Forge.)

It is proper to note, for those unfamiliar with the terrain, that sounds in this region carry in uncommon fashion. The outlet dam at the lower lake holds both waters higher than old recollection and makes a long mill-pond of lake and strait together—conditions that return an echo along the banks where the current constricts. In such a place a single bray may be thrown back upon itself again and again until a hearer would swear to a chorus when there was only one voice. Last night it was so—if it was not something else.

The reader will expect from me, as from any OLD SETTLER, some account of the man at the center. Mr. St. Germain is one of the earliest residents about Chazy Lake, a guide, hunter, and camp-cook of repute; he is as often praised for service as censured for independence. Those who have lodged with him will say his pan-trout and johnny-cake are a credential in themselves; those who dislike him point to his irregular hours and his habit of solving a difficulty first and answering for it later. In short, he divides opinion—healer or host, informant or thief—without ever quite resolving into either.

The committee that went up the ravine—being farmers, a teamster, and one man lately in the sheriff’s employ—did not go idly. For some weeks we have had small losses: venison gone missing from lines, a keg mis-delivered and settled in cash of doubtful stamp, and a ledger page vanished from the lakeside account-book (more likely torn by a care-less hand than spirited away, but the word “vanished” travels faster than its correction). To this were added rumors of lights seen late near the cedar brake, and of payments made in rough metal strips as if cut from something half-smelted. The country will remember that long strips of lead with charcoal still upon them were once carried down from Lyon Mountain by those who knew a certain cavern; the story of the erased trail is part of our common talk, and contributes nothing to calm deliberation when cries are heard at night.

Here the record must be plain. No unlawful spirits were found; no counterfeit press; no foreign tobacco; only a deer, properly dressed, a tired man, and a vigilant donkey. The constable’s book gives: one knife, one horn, one length of rope, one small flask, and a pocket-note torn through the center by damp. Mr. St. Germain was released on his own recognizance, pending any further statement by the game warden.

Yet the alarm has left marks. At the Forge, the wire operators report a peculiar tapping at the very minute the cry was first heard, though no message was made of it at the time; such incidents are logged now as a matter of routine. The dam-keeper, hearing of the disturbance, walked the crib at sun-up and found nothing out of place; the lake stood its usual rise, the flow free and regular.

Two notes remain for our sporting and traveling friends. First, the cedar gully is a deceptive place for sound. A bird’s call at the bottom climbs the slope and returns upon you as if from the opposite side; a man at twenty rods appears to be nearer when he is farther. Second, the donkey in question, though small, possesses a capacity of voice out of proportion to his size. One gentleman of the party, not given to fancies, declares that the animal’s cry, taken on the echo once, then twice, then thrice, set his lantern-glass to buzzing, and caused in his chest the same pressure a steamer’s whistle will sometimes give when one stands too near the works. Whether this be exact in the terms, it is certain the sound was strong.

To the inevitable question what, then, was heard?, the paper may answer thus: a donkey’s bray, returning upon itself; a deer, honestly taken; and a party over-ready due to recent rumors and the hour. If there is a crime in it, it is only that the law must be roused when a cry is heard, which is no crime but a duty. If there is a mystery in it, it is the old one of our woods, where a trail made boldly on one day is erased the next and where the ear is often less reliable than the hand. The cavern, if such there be, remains undisclosed—as certain men in former days learned to their cost when marked signs disappeared and even garments hung in trees could not be found upon return.

Conclusion.—The affair is closed for the present. No indictment is sought. The doctor’s report is favorable. The constable’s docket will show a caution only. But let it be entered in the county’s curious annals that on the 11th of this month, at the north end of Chazy Lake, the cry taken for mortal distress was produced by an animal of small value, and that the sound, by reason of banks, dam-pond, and night air, was so augmented as to be taken at the Forge for a signal upon the wire—an occurrence without injury but with much talk.

Respectfully submitted for the information of the sporting public and our neighbors,

OLD SETTLER.

What mysteries of Chateaugay Lake haunt you?