The Prohibition Era in East Bellmont: Bootlegging, Corruption, and Unearthly Shadows

By Mordecai Vilecreek — For The Steamboat Dispatch

Prohibition in East Bellmont wasn’t just about a dry spell without alcohol. It was a time of struggle against a national mandate, turning the Number Five Road and the South Inlet into battlegrounds where government men, bootleggers, and hard-faced preachers all clashed while the fog rolled low.

Artifacts of that era still linger—cracked jugs in the mud, charred beams under collapsed kilns, cellars bricked in haste. The town claims to have shed the crime and shame, but the woods don’t lie: they still hum with what was done there.

The Irony of Prohibition

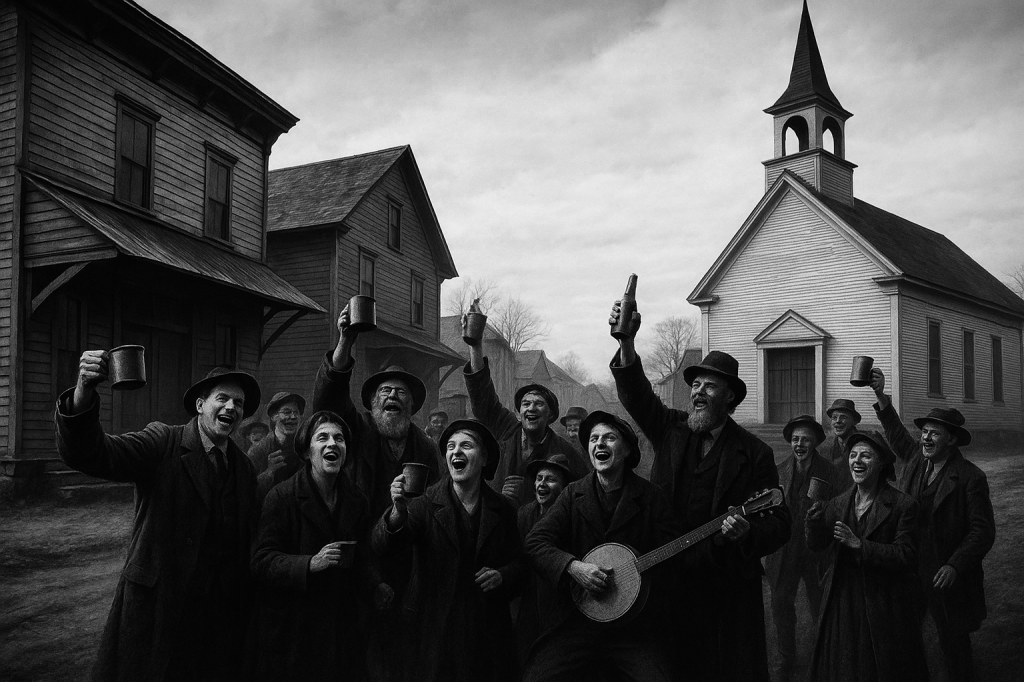

The irony was that Prohibition, meant to still the thirst, instead multiplied it. With every barrel outlawed, two more sprouted hidden.

In July of 1917, the Dispatch noted grimly: “Men drank who never drank before; women thronged the clapboard dance-halls; boys not yet grown reeled along the Narrows Road.” What was supposed to cure vice only bred more of it.

East Bellmont did not submit when the law tightened. It dug deeper. Cabins became speakeasies, barns turned still-houses, ravines glowed with lanterns. The quiet lanes throbbed at night, a covert town humming beneath the lawful one.

Cinder Row—the slag-blackened lane by the South Inlet—buzzed with a wickedness that could rival any city’s sin quarter. Its lamp-lit storefronts were masks. Behind them lay trapdoors, false walls, and the muffled revel of forbidden nights.

The Underground Economy

Through the 1920s and 1930s, the shops of Cinder Row doubled their lives. Soda counters by day poured whiskey by night. A boy could buy a lemon drop at noon, and by dusk his uncle might draw rye from the same counter’s hidden pipe.

One grocer bricked a false wall into his cellar, concealing a copper still that fed into the plumbing. Twist the pump handle, and whiskey flowed as if the very house bled it.

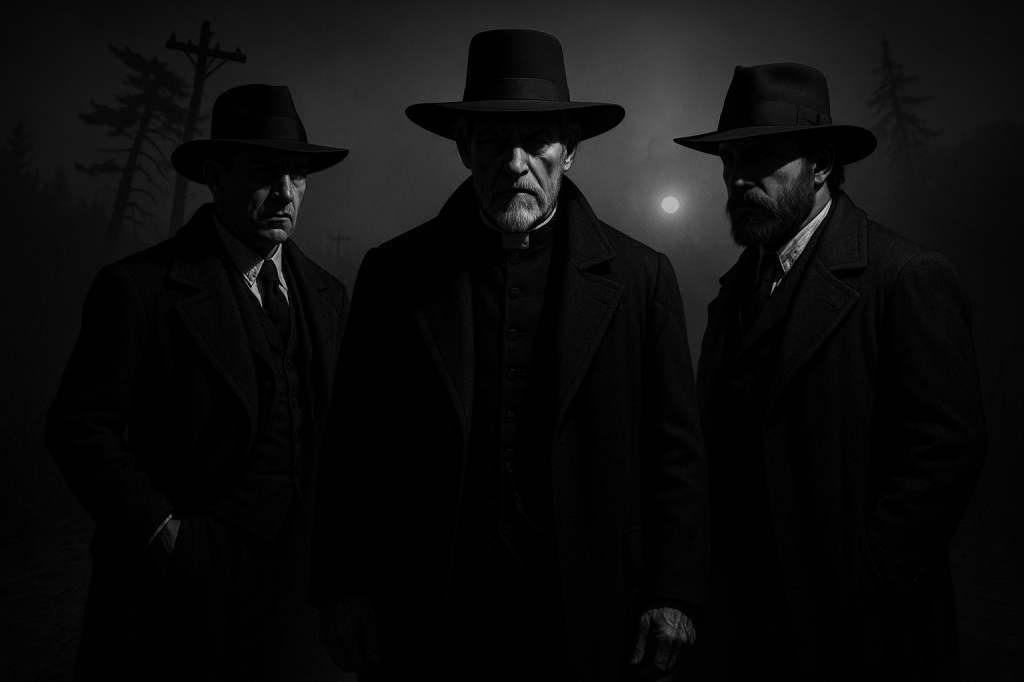

Deputy Allen Croff gained repute for sniffing out such places. He rode slow with his wagon window open, claiming he could smell mash boiling miles away. “You’ll smell ’em afore you see ’em,” he said. Folks repeated it. Others muttered that he wasn’t smelling grain at all, but something ranker rising from damp soil.

Corruption

The fight against the Dry Law never stayed in cellars alone. Corruption spread up through the ranks: constables bribed, clerks paid off, ministers preaching temperance on Sunday while tipping glasses by lamplight.

In 1933 came the great reckoning. Indictments rained down, names once trusted dragged through muck.

Among them: Mayor Darius Crump and Chief Constable Ed Merrill—charged on hundreds of counts tied to the liquor trade. Their ledgers and letters told enough to damn them, though townsfolk whispered that what really bound them was darker than whiskey money.

Cultural Reflection and Legacy

East Bellmont claims it has grown past all this. Today, Cinder Row hosts craft shops, eateries, and Friday artwalks. Families wander the Saturday market; fiddles scrape through the Twilight Concerts. Lanterns glow warm on painted fronts, and the air smells of fry bread instead of mash.

The merchants speak proudly of the ForgeBlock redevelopment, promising a boutique hotel, new offices, and tidy shops where the kilns once smoked. Crews drive nails, beams go up. Yet when a hammer strikes hollow, it sometimes reveals a second wall, a sealed pipe, a blind chase in the floorboards. These are the reminders.

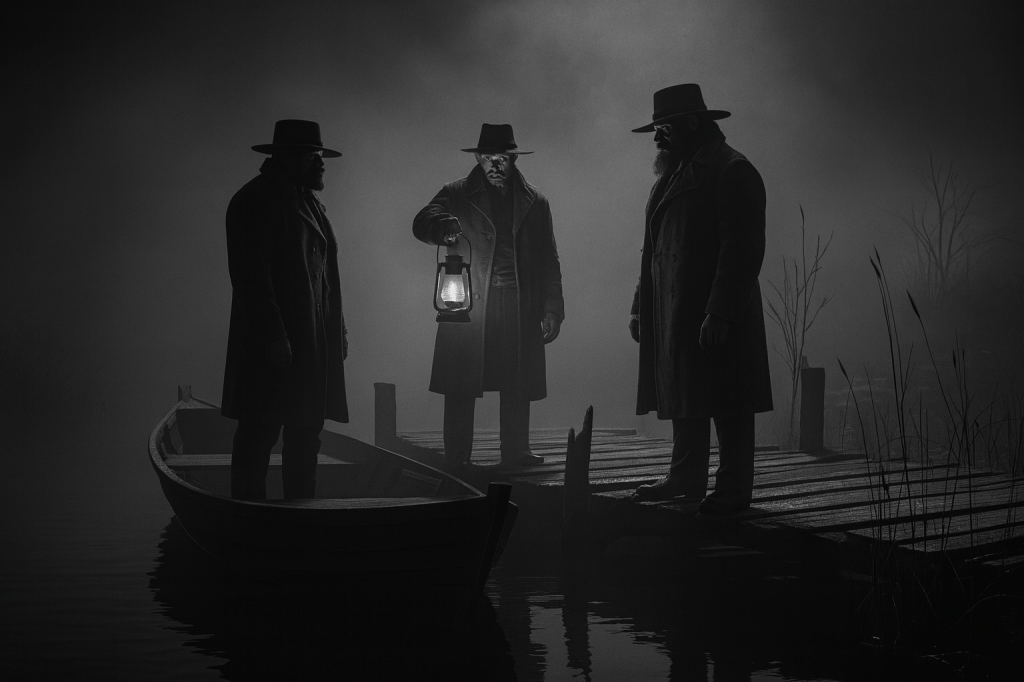

The lake does not keep books; it keeps silence. Step to the South Inlet at dusk and you’ll feel it—the still pull, the sense of listening without ears. The water does not record names, only shapes: lantern-smears drifting across the chop, the hiss of something boiling where no fire burns.

Builders may raise hotels, merchants may clap on paint, ministers may thunder from pulpits. Still the inlet waits, quiet and patient. And if you linger too long on the fogged edge, the past won’t be written down. It will be there beside you, wet-handed, waiting.

What mysteries of Chateaugay Lake haunt you?