DISTURBING THEMES ALERT: Includes detailed exploration of filicide-by-proxy, cult-like mob consensus enforcing human sacrifice, innocent terror and resignation, ancient curse consequences, graphic animal substitution slaughter, and pervasive existential horror tied to vengeful Adirondack wilderness spirits. Not suitable for all audiences.

Old Asa Bellows stood outside his camp, coat only half done up, jaw working hard like he was chewing on iron. Beside him was “Rope-Hitch” Gadway, the white-haired French-Canadian teamster who had fled Quebec overnight during the Patriotes Rebellion and now hauled ore, barrels, and misfortune all over the North Country. He held a lantern, its flame jumping, throwing shadows that twisted like old ghosts.

“C’mere,” Asa said low, as if the lake might catch the words. “Stand where I can see ye plain.”

Rope-Hitch stepped closer, eyeing the flat calm. “Oh, by golly, Asa—what beeg new trouble you sniffin’ now, eh? You look long time into dat black, oui—too long, I tell you—and pretty soon dat black, she look back at you, ho ho… maybe she call your name, soft-like, jus’ so.”

Asa pointed through the dark branches clawing at the sky. “See that star hanging low, like it has business dipping into the water? It’s hungry tonight.”

Rope-Hitch squinted, a chill running up his neck. “Ah ha. Dat be de Dog Star, oui—he slide past de Seven Sisters same way he do since beeg long time. Same, same… or maybe not, eh? Sky, he don’ care one bit ’bout yer belly feelin’ all heavy wit’ guilt—by gar, why he should? But… ah… when de lake, she put her han’ in de matter—ho, ho—den you look again. Maybe sky, he wink. Maybe he move jus’ de hair. You don’ swear on it. You jus’ feel it in de bones, like ice comin’ early.”

The lake stayed too quiet—no loons crying their lonesome calls, no waves breathing soft. Just a thick hush, the kind that rolls in before a snow squall… or something older stirring up from below, unasked.

“Ah ha. Why you out here so, hein—walkin’ like a man what done misplace he’s own name, eh?” Rope-Hitch asked. “De fellas, dey sleep. All of dem. Even de watch down by de landin’, he no stir at all—like somet’ing got ’em, grip-grip-grip, tight as a beeg fish in de net, ho ho.”

Asa let out a rough breath, scraping like bark, with a faint echo off the water. “I envy ye, old man. I envy anybody who lives quiet and dies in the same boots. Being small is sweet—small enough to slip past whatever’s watching.”

Rope-Hitch snorted, but his eyes flicked to the glassy surface. “By gar, I tell you dis straight, eh—small t’ings, dey don’ run from sorrow. Dey jus’ keep it quiet, oui, so de paper man don’ print it—and maybe, jus’ maybe, de lake she don’ get her hands on it yet.”

Asa pulled a sealed letter from his coat, tucked it away, then yanked it out again like it burned him. “There’s trouble. Big trouble, with my own kin mixed in—and something unnatural pulling the strings.”

Rope-Hitch’s voice eased a bit, though the lantern shook. “Say it now, quick-quick, before de night, she bend her ear and take it for herself, oui?”

So Asa told it, words hanging heavy like fog that won’t rise.

Years back, downriver, a scandal broke—a flirtation gone sour into a feud, full of talk about curses. A young woman from the French Settlement Road had run off with an outsider, and men from a dozen families swore they’d have vengeance: any stranger taking what was spoken for would answer with iron and fire, or worse—the land’s own anger.

Now boatmen, hunters, ore-haulers, and loud talkers from every shore camp had gathered at the lake with skiffs, bateaux, and plenty of brag, set for a hard march—part pride, part payback, part fear of looking weak under that staring sky.

Asa, with his good name tied to the Forge crowd and road bosses, got pushed up front as “captain” of the riled bunch.

But the wind wouldn’t come, like it was chained.

Day after day, the lake stayed flat dead. Fog hung thick as a burial cloth, whispering old warnings in the men’s ears—bits of tales about waters that hunger for balance.

That’s when the seer showed—not some far-off oracle, but Seth “Powder-Horn” Kirby, a local tracker from outside Crompville who knew cedar swamps and how to stir a crowd. He’d learned from Abenaki folks the old ways: respect, cautions, warnings about breaking balance—and what it costs when spirits wake.

By the beach opposite Bluff Point, where pines met sand, roots twisting like veins into the ground, Powder-Horn said: “This ain’t no weather, not by a long shot. It’s a lock snapped shut on the whole world, set there by somethin’ older’n any oath ye ever swore. The lake’s got its hands round yer windpipe ’cause somebody’s settin’ harm in motion with a soot-black heart—and it’s stirred up somethin’ down deep in that Lab’rynthe what oughta stayed asleep.”

Then the hard part, with eyes shining like moonlight on water: “Fer passage—fer the wind’s say-so—you give the lake what it’s askin’: a life off the leader’s own roof-tree. That’s the old rule, same as frost an’ gravity. Balance don’t dicker with yellow bellies; it takes what’s owed—or it takes extra, interest an’ all..”

Rope-Hitch listened, face turned away, feeling the fog creep closer.

Asa swallowed, tasting fear like metal. “So I wrote my wife, Martha—told her to bring our oldest girl here for a fine match, a proper union. A lie dressed up nice, but the lake seemed to demand it.”

Rope-Hitch gripped the lantern tighter, flame sputtering like it objected. “Ah ha—ye spin de weddin’ story, hey? To settle what, now—de water, non? By gar, dat lake, she don’ care. She stir, she stir, same all de time. Ho ho.”

Asa nodded, miserable. “A sham. Ribbon round a knife, dangled for eyes that ain’t human.”

He’d baited young Noah “Quickstep” Merrill—a decent runner and fighter—without the boy knowing, while the fog thickened like it lived.

But Asa’s conscience kicked up, too late, as shadows grew long wrong. He wrote a second letter to stop the first, begging Martha not to come. He pushed it at Rope-Hitch.

“Run it to the Road Forks by Wolfjaw Cut,” Asa said urgent against the silence. “If ye spot their wagon, turn ’em back. Don’t stop for water—don’t let sleep catch ye, or worse. Beat my foolishness there, before the lake claims its due.”

Rope-Hitch took it, glancing at the water’s edge where ripples started for no reason. “Ho ho!—what if dat Martha, she look at it sideways, eh, an’ say, “Bah… mebbe dat t’ing ain’t real at all, by golly?”

Asa showed the seal. “She’ll know my stamp—even if the night tries to fake it.”

And Rope-Hitch went into the dark, swallowed like a promise.

The Women Arrive

Soon women from the early settlements now turning into hamlets—wives and sisters of the workers—gathered on the sand, watching the camp like kin over a sickbed. Their talk stayed soft, but eyes sharp, seeing the greased-up men, stacked gear, and shore turned staging ground for trouble—while fog whispered doubts.

Then the wagon rolled in out of the mist like a ghost rig.

A mill sawyer ran up, ahead of the rest: “They’re here! Yer wife, yer gal, an’ yer boy too. Folks reckon it’s a weddin’—but the air don’t set right!”

Asa’s face went pale as moon on still water. “The world’s beat my regret—and the lake’s pulled ’em in.”

Martha came proud but tired, with dowry bundles, food, and the sleepy boy. Elsie Bellows jumped down, hugging her father like the world was still safe—unaware of the dread creeping up from below.

“Papa!” she called, voice echoing strange across the flat.

Asa held her tight like a drowning man to a log, feeling the water watch.

The Lie Unravels

Quickstep Merrill wandered up, puzzled by talk of his bride, words twisting like smoke. Martha greeted him warm, figuring thanks.

“Ma’am… I ain’t rightly sure what you’re gettin’ at.,” he said, shivering as fog brushed him.

Rope-Hitch burst in, eyes wild, whispering to Martha: “Ah—you right. My mistake. Lemme set it straight, plain talk, no sing-song. Dis ain’t no weddin’, no ma’am. It’s a killin’, all fixed up in lace, called on by t’ings we had no right to rouse in de first place.”

Martha froze, cold to the bone, like the lake touched her soul.

The camp’s stirrers—eager for “history”—muttered the sacrifice had to go on, or they’d be North Country fools, voices rising as mist thickened.

Slick Deke “Slyboot” Hoit worked the crowd with talk of “duty” and “honor,” saying the leader’s family pays first—words sliding like tendrils from deep.

Martha faced Asa amid women, sand, and whispering pines: “Ye’ll kill our girl to settle a crowd? A story? Yer pride—or whatever’s in that water?”

Elsie heard, putting it together. Her cries cut raw, piercing the quiet, seeming to stir faint answers from the lake.

She begged her father with words that shamed the men, pleas hanging like signs.

Asa, cornered, muttered: “If I don’t, the mob’ll tear us apart. Burn the house. Kill ye all. The lake’s boxed us—its will can’t break.”

Quickstep pushed forward: “Ye used my name to draw a young’un in, like bait on a hook, just to feed somethin’ nobody’s s’posed to see?”

He swore to fight, but the crowd pushed back—not fists, but angry agreement. A hundred nods, then a thousand “yeahs,” increasingly uglier and louder in the growing shadows. Quickstep knew that scared mobs make cowardice law, especially under a “cursed” Shatagee Lake sky.

Elsie’s Resolve

Then—the turn that made ’em tell yarns down ta Abner’s Forge store fer years after—Elsie stopped her crying as a sudden cold wind teased the fog edges.

She straightened, wiped her face, and told her mother: “Ma, don’t make it worse begging like they’re kings. If they’re set on this, I’ll go quiet—afore the lake takes us all.”

Martha shook, heart thumping, feeling the water quicken.

To Quickstep, Elsie said: “Don’t die for me. Don’t give ’em another reason—or stir ’em up more.”

She walked to the grove by the shore pines, where bowls, meal, and knives waited like ordinary things, ancient fragrant balsalm trees swaying and rustling like they waited too.

An Abenaki elder, Wôban-giizis—Morning Moon—had stayed near, keeping out of white men’s quarrels unless the land got offended. He didn’t yell or argue; he watched the lake, eyes holding depths that moved unseen.

And the lake watched back, surface rippling faint, like something waking.

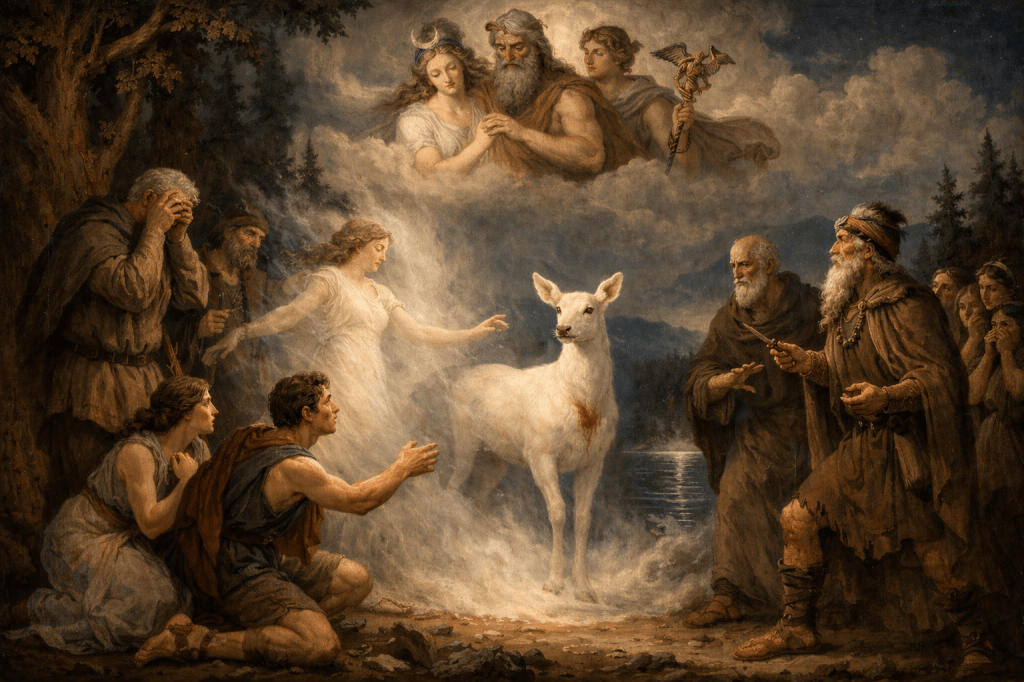

The Switch

They led Elsie into the grove, air thickening, charged with a vibration seemingly from nowhere. Asa looked away, weeping behind his sleeve, ashamed of his hands—and what he’d called up.

Powder-Horn lifted the knife, blade catching starlight that pulsed.

A thud—like a dull hit on wet wood, echoing from below.

Then… no Elsie.

Not gone like magic, but like the world—and lake—had changed her fate, air shimmering with strange light.

In her place, a big white-tailed doe thrashed, wild-eyed, blood where innocence bleeds under men’s “justice”—eyes holding a human look that faded like fog.

Powder-Horn stared, knife falling as ground trembled light.

Morning Moon spoke low, voice carrying old weight: “Da lake, she no eat flesh—she trade names, an’ she keep what she’s owed.”

Then wind roared in like a gale, fierce and living, shoving boats, slapping flags, churning waves, reminding men how small they are—and carrying far cries that might’ve been loons… or something else.

Aftermath

Adaline Bunker, a neighbor, ran up to Martha: “Yer girl ain’t dead—she’s tucked where the lake still shows mercy, hid away in its own folds. Don’t go askin’ how. I seen it, clear enough—and I felt it sittin’ there, watchin’ !”

Asa followed, gray-faced: “We got to go. The crowd’s turning this to brag, but the spirits won’t forget.”

Martha stood with her boy, torn between falling and rage, as wind whipped fog into shapes that stayed too long.

The shore women looked at the Narrows, where wind had opened the lake like a door to the unknown.

Somebody murmured, like prayer: “God’s ways ain’t what folks expect.”

Another answered, sharper, truer: “Ain’t God at all. It’s the lake—and it’s woke up now!”

What mysteries of Chateaugay Lake haunt you?