Banner House

Chateaugay Lake, New York

SHATAGEE LAKE STEAMBOAT GAZETTE CO.

East Bellmont, N.Y.

Dear Editor,

I HAVE read the yarn about the trouble at the Narrows on Chateaugay Lake, the one where they tried to offer up a girl to settle things with the water. It caught my eye because my own people have been tied to that lake since way back, and my grandfather used to tell stories about how the old lake never quite lets go of what happens on its shores—how it can break a family clean in two and then hand it back shaking.

I’ll tell it the way my father, Grimsap Vilecreek, used to tell it to me, straight, no fancy trimming. Back in the days when the lake still drew crowds for the fishing and the quiet, folks would come up in summer and camp along the points and bars. One fall, after most had gone home, a bunch got stirred up over some old notion that the water needed paying off—bad weather, poor catches, whatever it was that year. They figured a sacrifice might square it, and they picked a young girl to stand for it. My father always said that kind of thinking starts when men get scared and forget the lake’s just water, deep and cold, but not cruel unless you push it—until it looks at your own blood and decides.

My father knew the old guide Quickstep Merrill. This was back when he was young and spry. He was one of Lewis Bellows’ steady “Lake House” guides. Quickstep knew every rock, trout spring, and current from ice-out to freeze-up. Quickstep ran boats and led parties of rich sports back when the big camps were full.

During daybreak of the day the trouble broke out, Quickstep and some others were out on the point arguing to fight against the whole notion. My father remembered him saying it plain: “You don’t dress up murder with mist and call it holy just ’cause the body didn’t float up to prove you wrong.” And when they started grumbling he was soft or scared, Quickstep shot back, voice cracking with fury, “If keepin’ a kid from bleedin’ makes me your enemy, then you boys never were friends—just fellas waitin’ for the lake to pick sides!” My father said Quickstep stood his ground even when stones flew and the crowd turned ugly, voices rising like a storm coming on, hearts pounding so hard you could almost hear them over the water.

Another man who figured in it was Rope-Hitch Gadway, a big fellow from Quebec who hauled boats and broke ice in spring. Rope-Hitch backed Quickstep when things got rough. My father handed down how he bellowed at the men rushing in, voice raw and shaking: “Back off, tabarnak! You done fed one poor kid to dis mess already—how many more you gonna stack up, hein, before de water start collectin’ from de whole damn crowd, eh?” That stopped them cold, my father said, because nobody wanted to hear the tally when the lake might start keepin’ score—and nobody wanted to be the one who made a mother bury another child.

Martha Bellows was the girl’s mother, and she held like iron through every hour of it. She sat by the wagons, arms folded so tight her knuckles went white, telling anyone who’d listen that her daughter walked into the trees and she wasn’t leaving without her. When somebody muttered she was already part of the lake, my father remembered Martha snapping back, voice breaking on the edge of a sob: “Then let the damn thing bring her back to me. It’s swallowed bigger wrongs and coughed ’em up before—I ain’t leavin’ her down there alone.” No one dared lay a hand on her—not out of kindness, but because the whole shore was watching, and every man felt the ache in her chest like it was their own.

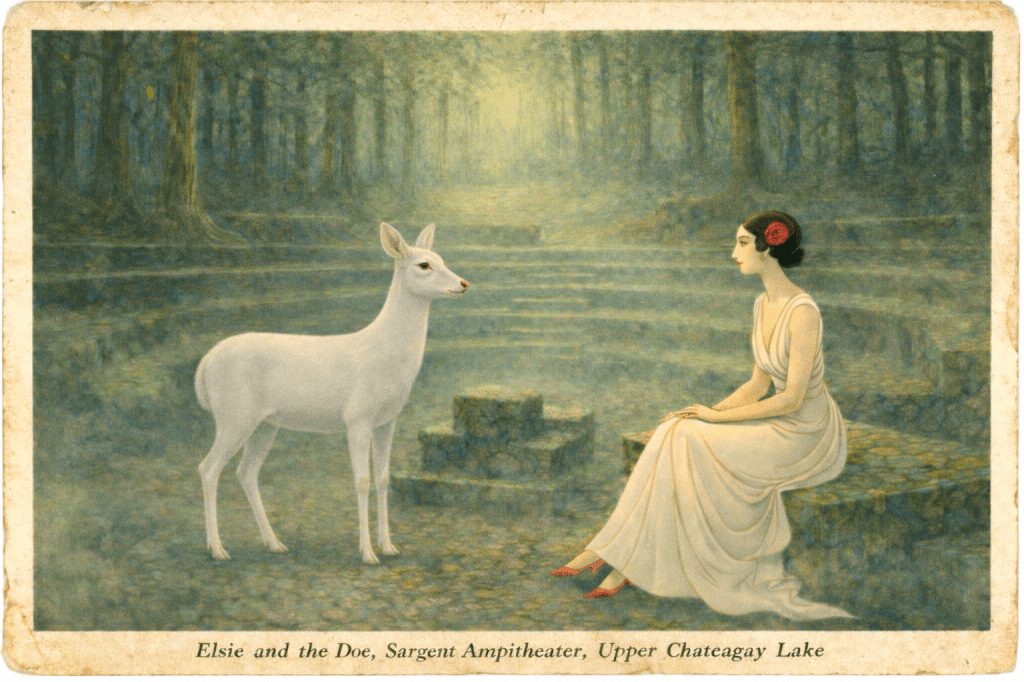

Asa Bellows, the father, tried to keep charge at first, giving orders like he still ran the show. But after the knife went in and the doe fell instead, something in him shattered. My father said Asa let his knife slide into the water as he watched Elsie disappear, in shame and disbelief—no throw, just open palm and gone, like he was giving the lake the last piece of himself he had left. Later someone asked him why, and he muttered low, voice thick with grief, “They’ll drown me for botchin’ it—but I can’t carry any more of her blood on me.” The crowd went quieter than they’d been all day, because they saw a man who’d finally broken open.

That night, after most boats pushed off, Martha went looking with a couple of the Abenaki women who knew the old ways and Rope-Hitch along for the lantern light. They walked the pine line slow, low lights on the needles, no tracks, no sign, only a braid of the girl’s hair left on a flat stone by the edge, tied with red thread like the river people use for protection. Morning Moon was there too, leaning on his staff. When Martha asked him straight, voice trembling now, “You know where she is, don’t ya?” he answered quiet, “I know de place where de lake, she make up her mind not to keep her—pas encore, not yet, anyhow.” My father said you could hear the hope and the terror fighting in her breath right then.

Near dawn the water moved—not wind, but something turning over deep down. The Abenaki women sang the old song, Morning Moon struck the surface three times, and the Narrows opened just enough—a dark path through the reeds. Out walked the girl, barefoot, dry, looking older in the eyes but whole. Martha’s knees gave out. A sound tore out of her—half scream, half prayer—that cut through the fog like a blade. She staggered into the shallows, water splashing cold against her legs, arms reaching, shaking so bad she almost couldn’t hold them up. Elsie saw her and ran—small, frantic steps—then crashed into her mother’s chest with a sob that shook them both. Martha clutched her like she’d never let go again, fingers knotted in hair and wool, face buried in the girl’s neck, breathing in the smell of pine and lake and alive child, tears soaking through everything. “My girl, my girl,” she kept whispering, over and over, voice wrecked.

Asa reached them in a rush, boots splashing, and dropped to his knees beside them. His hands—rough, trembling—cupped Elsie’s face, thumbs wiping tears he couldn’t stop from falling himself. He pressed his forehead to hers, shoulders heaving with great, silent sobs that rocked all three of them. The boy came last, tripping, scrambling up, and throwing himself into the knot of arms, clinging to his sister’s back, face pressed hard between her shoulders, choking out “Sis—Sis—” like he’d been holding the word in his throat for days. They stayed locked together in the rising shallows, water lapping gentle now, while first light touched them gold—no words left, just ragged breathing, small fierce grips, and the kind of relief that hurts worse than the fear ever did.

Later Morning Moon said it plain, the way my father always quoted him: “She was offered, sure—but de lake don’t take stole breath; she take de deer, ’cause deer b’long to de woods, kids b’long to deir mamas, an’ de water know de difference an’ don’ forget a lie.” And when somebody asked why all the trouble, he answered, “’Cause men keep pokin’ at somet’ing dat don’ need to prove she can take everyt’ing, oui.”

By noon the boats were gone, folks already changing the tale to make themselves sound better. My people stayed on the shore, watching the wakes fade, Martha still holding Elsie’s hand like it might slip away again any second. The old-timers around Chateaugay still say you can fool men and crowds, but you can’t fool water that remembers—and you can’t unfeel the moment it gives your heart back to you broken open and beating.

Mordecai Vilecreek

Banner House

Chateaugay Lake, N. Y.

to be continued…

FolkHorrorLakeLore AdirondackSacrificeTale WaterRemembersWrongs AbenakiLakeWisdom MaternalReclamationMyth DeerSubstitutionRitual NarrowsRedemptionStory SuperstitionVsSanity FamilyShatteredRestored ChateaugayHauntedShores

What mysteries of Chateaugay Lake haunt you?