By Clarissa H. Stark, Special East Bellmont Correspondent for the Steamboat Dispatch

Content Warning: Contains female sharpshooting on ice, discreet midnight executions, secret W.C.T.U. conspiracies, and the fragile line between zealous justice and vengeance. Mature audiences only; vivid bloodied snow, moral upheaval, and covert motives.

WILD GOOSE POINT, Chateaugay Lake, February 1924 — At the frozen narrows known locally as the Ice‑Cut Channel, the body of a known liquor smuggler was found in mid‑morning sun, his side perforated by a single pistol shot. This grim tableau marked the rough end of one rum‑runner’s career—and cast suspicion not only upon rival gangs, but upon a clandestine W.C.T.U. presence long whispered to be operating in the shadows of East Bellmont. Sources suggest the agent code‑named Swan of Larrabee, a determined daughter of the Kirby family, may have delivered that fatal shot.

Prohibition’s icy frontier

Since the Volstead Act took effect in mid‑July 1920, the waters and frozen channels of northern New York have become arteries for smuggling operations. Rum‑runners plied remote wooded coves under cover of darkness, delivering whisky and rum from Québec across the ice or via stealth launches. Federal patrols have responded by seizing speedboats near Long Island’s Rum Row, engaging in midnight chases and exchanges of gunfire that left multiple casualties. Less is known about enforcement on inland lakes—but on this frozen local lakebed, lawlessness paid a price.

Discovery at Wild Goose Point

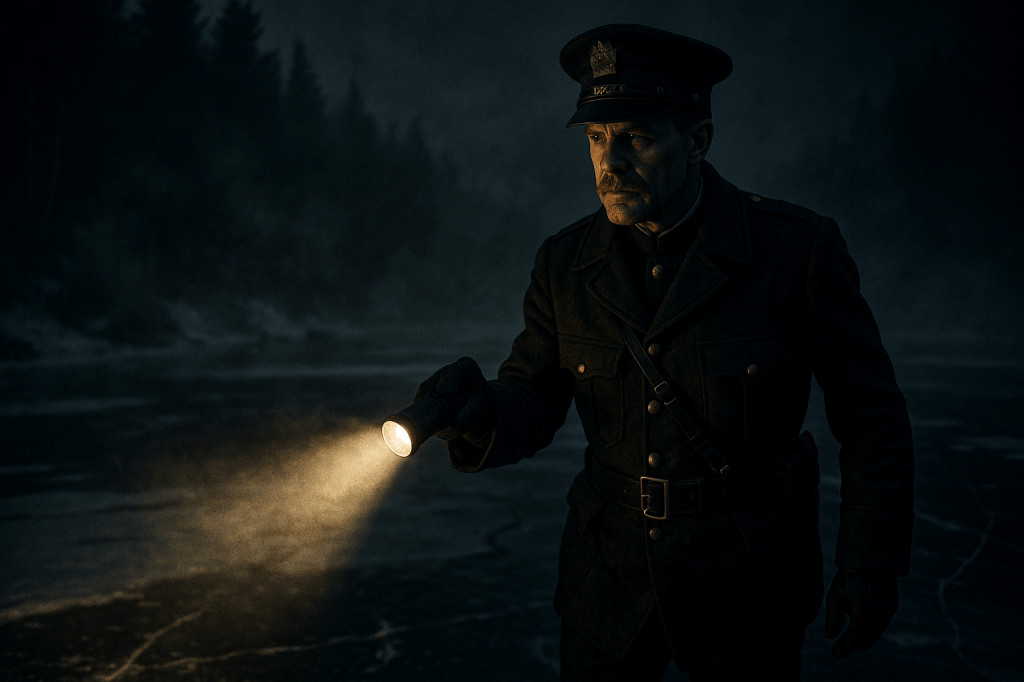

Shortly before dawn on February 2, Constable Harold Moffatt of Malone was summoned to the Narrows, where a sleigh had apparently overturned. At first light, the half‑frozen remains of Francis “Frankie” Marigny, a known smuggler from the Malone roadside rings, were found still clutching the reins. A neat bullet wound in his right flank suggested the shot was not accidental.

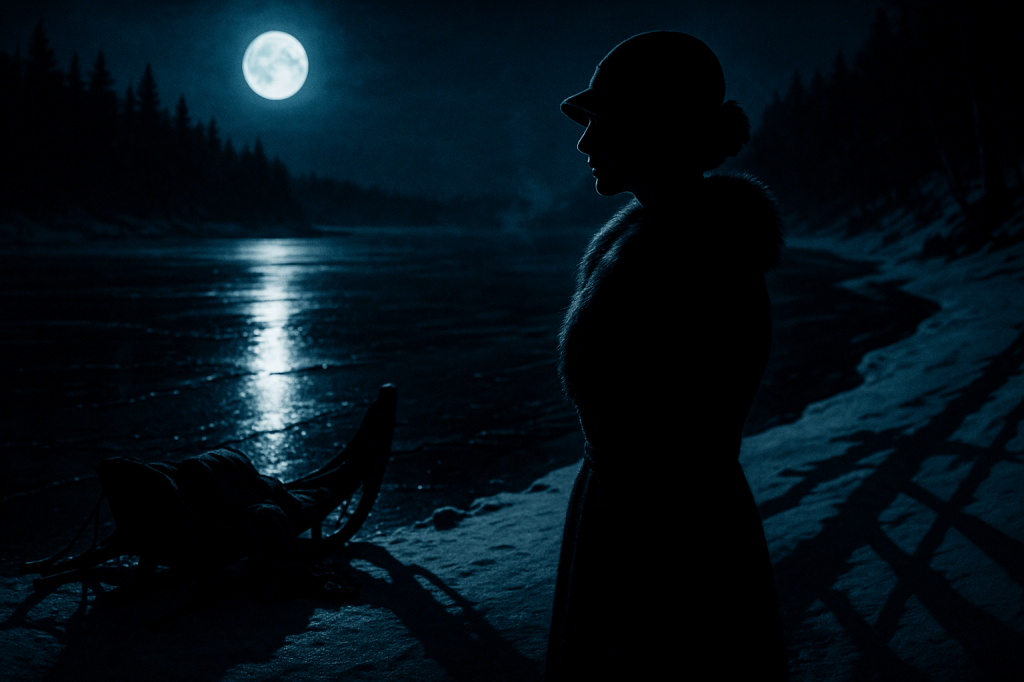

The frozen sleigh runners nearby bore footprints not matching Marigny’s party—small‑footed prints, likely female, and no sign of a second large boot. A discarded silk scarf, patterned with lilies and bordered in emerald green, lay trampled in the snow.

Investigation: Gang feud—or Temperance justice?

Two lines of investigation emerged: first, the possibility of a smear between rival rum‑runner factions; second, whispers in Brainardsville and Bellmont that an operative of the Secret W.C.T.U. East Bellmont Chapter, known only as the Swan of Larrabee, had taken matters into her own hands.

Local women of impeccable reputation—Miss Esther Kirby and her cousin Miss Verity Kirby—have long been suspected of covert resistance. Through coded telegrams concealed in hymnbook margins and whispered confections in church bake sales, they are said to coordinate intelligence and occasional sabotage. The sobriquet “Swan of Larrabee” refers to their knowledge of the swamp and ice channel trails, where the pioneer training passed down by their settler ancestors and honed through long hours of practice, endowed them with uncanny skill in following snow‑horses or placing marks on sleigh flanks without being seen.

Moreover, forensic detail supports an orderly shot: investigators noted no sign of struggle on the victim or sleigh, and the bullet trajectory suggests a shot from slightly behind and above, as if delivered by someone steady and confident—not a panicked gang assassin.

Local historians weigh in

Dr. Lucinda Phelps, independent chronicler of local lore, described the event: “Rum‑running in Chateaugay Lake owes its life to secluded ice corridors like Wild Goose Point. Yet an agent with superior knowledge of terrain and winter craft—especially one raised tracking deer through Larrabee Swamp—could intercept a convoy unobserved. One only has to recall Kimabeth Kirby’s memoir of trailing raccoon in men’s moccasins to see how such a feat might be done.”

Captain Edwin LeMoyne, retired from the Old Guide’s lodge at Merrill House, noted: “The shot was clean; it echoed across ice that holds sound like a vault. A rival gang war would likely involve multiple shots or more violence. This was surgical.”

Church Ladies as covert avengers?

That sober Brainardsville women might resort to firearm action remains incendiary. Yet such speculation resonates with the earlier transformation of their W.C.T.U. chapter—from quilt meets to covert field agents—as detailed in private intelligence manuals. These ladies, taught in discreet gun practice and trained in the ways of silence and disguise, have carefully studied smuggler garb, slang, and habits to slip unnoticed into inns and launch docks. Their handbags, it is said, hid compact Psalm booklets alongside pocket revolvers.

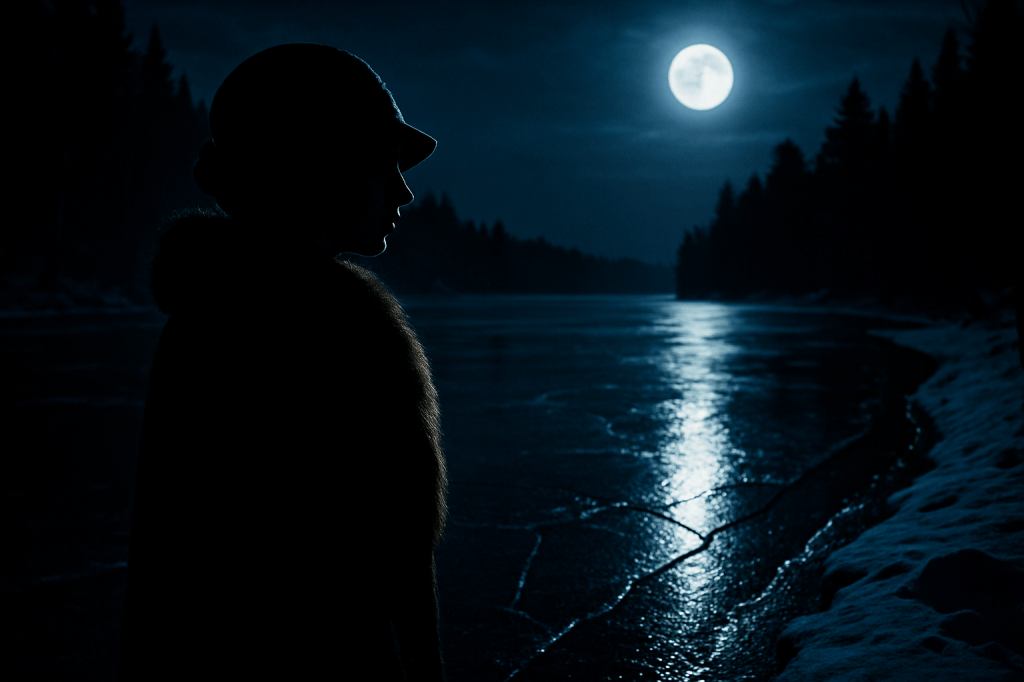

Some townsfolk report seeing a woman in mink stole and spaniel hat wait beside the narrow ice bank the previous night, only to slip away when approached. No one saw her face—but she carried herself with the calm bearing of someone entirely confident in what she carried beneath her muff: a mission.

Cover‑ups and coded testimony

Constable Moffatt’s official report remains circumspect, merely stating Marigny died by gunshot. Yet several lines of testimony, gathered separately by local constabularies and posted on bulletin boards at the Owlyout Tavern and the Rocky Brook Camp post, hinted at more.

- A stable hand reported seeing Marigny unhitch his sleigh at nearly midnight and walk toward a concealed wood pile. A woman’s voice called to him—but when he replied, only one figure lay on the snow soon after.

- A tavern waitress claimed she served Marigny a tumbler of “golden stuff from Québec” hours before; afterward, he stiffened suddenly, nearly choking.

- A woodsman at Rocky Brook Camp said he heard a single muffled shot near the narrows at about 1 a.m., followed by soft footfall retreating off the ice.

Smuggler networks shaken

Marigny’s death triggered panic among inland smugglers. Two scheduled crossings that week were canceled, high‑risk routes were abandoned, and tavern talk turned toward unseen local resistance rather than rival operators. If a young church lady—not a lawman—could deliver such a blow, many speculators decided to flee rather than stay.

Meanwhile, deputies in Malone discreetly collected rumours but publicly offered no reward—or credit. The local press ran the death as “tragedy on the ice,” with restraint. Only The Steamboat Dispatch, long sympathetic to bois‑du‑roi tales and frontier lore, printed the speculation tying it to the secretive “Swan”, prompting fervent interest.

A new kind of justice on Chateaugay Lake!

Whether Marigny fell by gangland vendetta or Temperance vengeance may never be known without confession. Swan of Larrabee, with her tracker’s skill, her knowledge of ice and thorn, may hold the answer—though she has spoken to no reporter.

What is certain: the smugglers whose cunning once brought whisky across frozen lake and forest trail now face an adversary unlike any before—women raised in church pews who learned how to mingle with criminals, to mimic their garb and speech, and to strike with hidden resolve when the moral moment demanded it.

Thus does Prohibition’s reach draw strange allies and strange foes to Chateaugay Lake: from the steamer docks to the frozen narrows at Wild Goose Point, justice now wears a swan’s quiet grace—and carries a .22.

This full‑feature dispatch, illuminates a pivotal incident in the post‑Popeville narrative: one where frontier piety meets frontier tactics, and where the steamboat syndicate’s downfall may hinge on the icy precision of one resolve‑fueled woman in mink.

What mysteries of Chateaugay Lake haunt you?