In the shadowed hollows below the old Standish ironworks, where the Separator Brook twisted through a labyrinth of rusting slag heaps and acidic ponds, the land had long borne the scars of human ambition. By 1883, an eight-fire bloomery had clawed iron from the earth, its hammers pounding day and night until the pig-iron blast furnace rose in 1885, belching smoke that stained the sky. What remained were tailings dumped heedlessly into the marsh: jagged slag, leaking oil drums, and smelting refuse that leached into the soil, transforming fertile wetlands into a fetid morass. Oily reeds choked the banks, dead fish bobbed belly-up in iridescent slicks, and low fog clung like a shroud, carrying the acrid tang of fermenting debris. This was no mere wasteland; it pulsed with a reactive malice, as if the earth itself judged the trespassers who had poisoned it.

Zenda Crane knew the swamp’s rhythms better than most. A lone trapper eking out a living on its margins, she was iron-willed and practical, her days spent setting snares for muskrat and beaver amid the twisted willows. Versed in the lore of the North Country—half-remembered tales from the Abenaki of mud demons stirred by tainted ground—she relied on folk remedies: boiled willow bark for fevers, poultices of cattail root to draw out poisons. Zenda trusted the stories passed down through generations, whispers of spirits that guarded the balance, awakening when the land was wronged.

In contrast stood Captain Harlan Voss, a roughhewn riverboat pilot turned liquor smuggler, one of the infamous steamboat pirates who navigated the Chateaugay Narrows’ hidden channels. Skeptical and profane, with a scarred face from boiler explosions past, he dismissed tales as the ramblings of the uneducated. “Crude instruments tell the truth,” he’d growl, fiddling with his broken barometer, mercury vials, or the hand-cranked magnetometer he’d salvaged from a derelict foundry. It was meant to detect buried iron or chemical anomalies, and to Harlan, that was science enough—far superior to herbs and superstitions. Their paths crossed often in the borderlands of law and wilderness, breeding a rivalry that was cultural, epistemological, and deeply personal: she saw him as a despoiler, dumping contraband into the brook; he viewed her as a backward relic, clinging to myths in a world of progress.

The trouble began one mist-shrouded autumn when Harlan’s pontoon, laden with smuggled oil drums to mask his moonshine cargo, struck a submerged slag pile. Several barrels tumbled overboard, splitting open and spilling their viscous contents into the mouth of the Separator. The ecosystem turned wrong almost immediately. Fish sickened and floated in grotesque clusters, their scales peeling like rusted metal. Frogs swelled unnaturally, their bodies bloating until they croaked in eerie unison through the night, a chorus that echoed like distant machinery grinding to a halt. Strange heat pockets bubbled beneath the mud, glowing faintly as if the earth’s veins ran with molten residue. Whispers spread among the locals of a massive furred shape sloshing through the shallows—part giant muskrat, part bat, part something dredged from primordial ooze. They called it the Bog Fiend, but in the North Country vernacular, it became “the Slagscrag,” a name evoking the jagged waste that birthed it.

Zenda glimpsed it first, while checking her traps at dusk. A slick-furred form, wing-armed and claw-handed, reared from the reeds, its body a grotesque fusion of bear bulk, mosquito proboscis, and bat membrane, warped by the contamination that seeped into every pore. It fed on carrion and poisoned fish, its maw emitting faint sparks that ignited dry grass, and its hide glowed with an industrial phosphorescence, as if slag had infused its very bones. This was no mere beast; it felt like the swamp’s retort to abuse, an entity awakened from ancient strata, hungry for retribution. Harlan scoffed when she warned him over a shared fire at the river’s edge. “Your mud demons are just fever dreams from bad water,” he muttered, cranking his magnetometer. Yet the needle spun wildly, detecting violent anomalies beneath the bog—buried iron, perhaps, or something worse, a magnetic fury that defied his instruments.

Their clash deepened as the Slagscrag’s predations escalated. Livestock vanished from nearby farms, dragged into the muck with trails of oily fur left behind. Zenda brewed rites from elder stories—boiling cattail and iron filings to ward off the spirit—while Harlan probed the ponds with mercury probes, convinced the disturbances stemmed from chemical reactions in the slag. “Science don’t lie,” he’d insist, but Zenda retorted, “Neither do the old ones. This ground’s poisoned, and it’s answering back.” Neither fully grasped the truth: the creature blurred the line between folklore and fact, a manifestation where industrial waste had roused something primeval, generative horror from contamination’s womb.

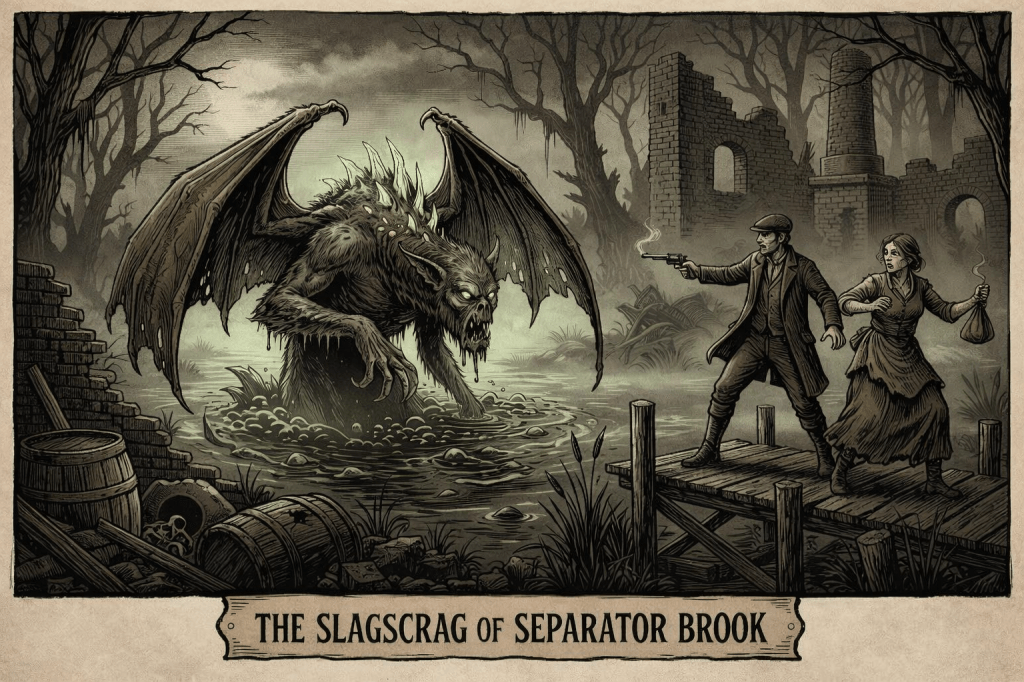

The pivotal moment came during a tense night watch by firelight, as Harlan guarded his latest moonshine cache on the pontoon and Zenda patrolled the reeds. The fog thickened, carrying distant echoes—a low roar like the Lyon monster’s fabled cry from miles away, and whispers of incendiary embers drifting through Bellmont’s woods, as if the forest itself stirred in sympathy. Suddenly, the Slagscrag erupted from the poison muck, its wing-arms flapping with a wet slap, claws seizing a moonshine keg in an act both absurd and terrifying. The barrel vanished into the depths with a gurgle, the creature’s eyes gleaming with unnatural intelligence, its breath igniting torchlight in brief, acrid flares. Harlan fired his revolver wildly, the bullets sparking off its slag-encrusted hide; Zenda hurled her boiled ward, which sizzled against its fur, eliciting a shriek that warped the air.

Survival forced uneasy cooperation. Harlan’s magnetometer guided them to the anomaly’s heart—a sunken bloomery ruin where slag ponds converged—while Zenda’s lore revealed patterns in the mud, sigils like Native warnings etched by the entity’s passage. Together, they confronted the Slagscrag in the glowing depths, its form dissolving and reforming in the acidic slurry, feeding on the very toxins that sustained it. They drove it back, not with finality, but enough to retreat, Harlan’s instruments shattered and Zenda’s remedies depleted.

This account, pieced from what we barely survived, serves not to explain but to warn. The Slagscrag was no isolated aberration; it whispered of a larger reckoning, where human trespass awakens the land’s unfamiliar forms. In the North Country’s poisoned veins, certainty collapses—superstition and science entwine in dread—and the swamps hunger still. Tread lightly, lest you rouse what lies beneath.

What mysteries of Chateaugay Lake haunt you?