She come cold, this story—like soot on your tongue, ho! If you’s afeared of shadow-creeps an’ bark that breathes, best skip on past, au plaisir de revoir!

From the East Bellmont Correspondent of The Steamboat Dispatch

Dateline: July 4th, 1895

Filed from the Charcoal Road above the Little Trout River

“Time is the moving image of eternity.”

— Plato, in Timaeus

It was some few hours before the first whistle of the log-train had cracked the morning fog when Mr. B. Haskett Fritch, the kiln-tender at Blair’s No. 4 Char Pit, noted a “swelling and folding” in the very color of the air above the Trout Crossing. He described it, rather more poetically than his usual demeanor suggests, as “a slow black grin in the shape of a memory.”

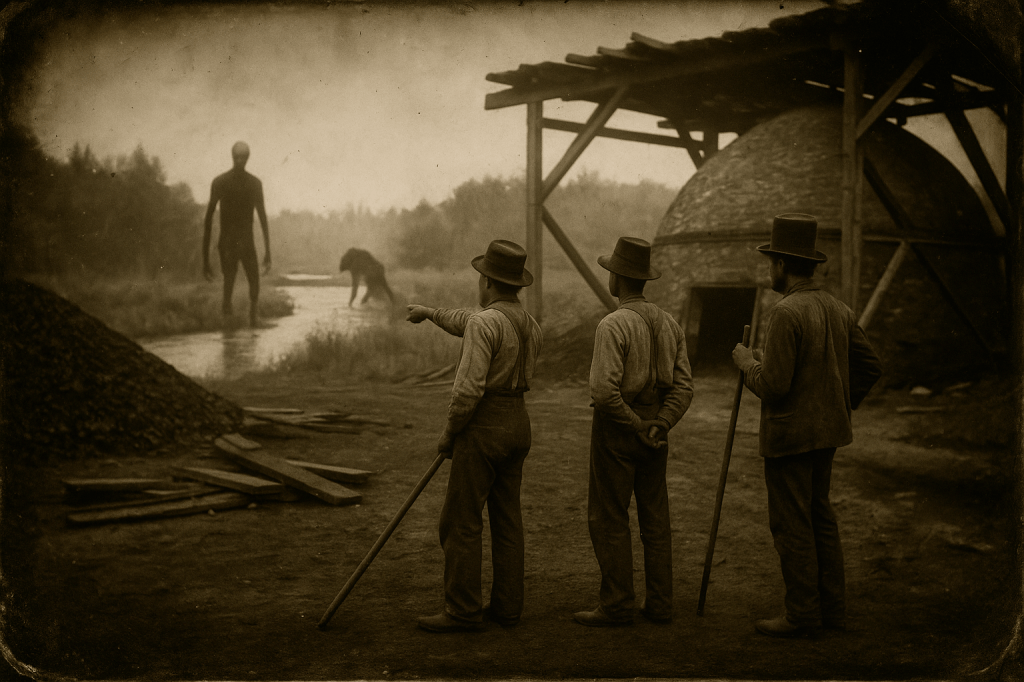

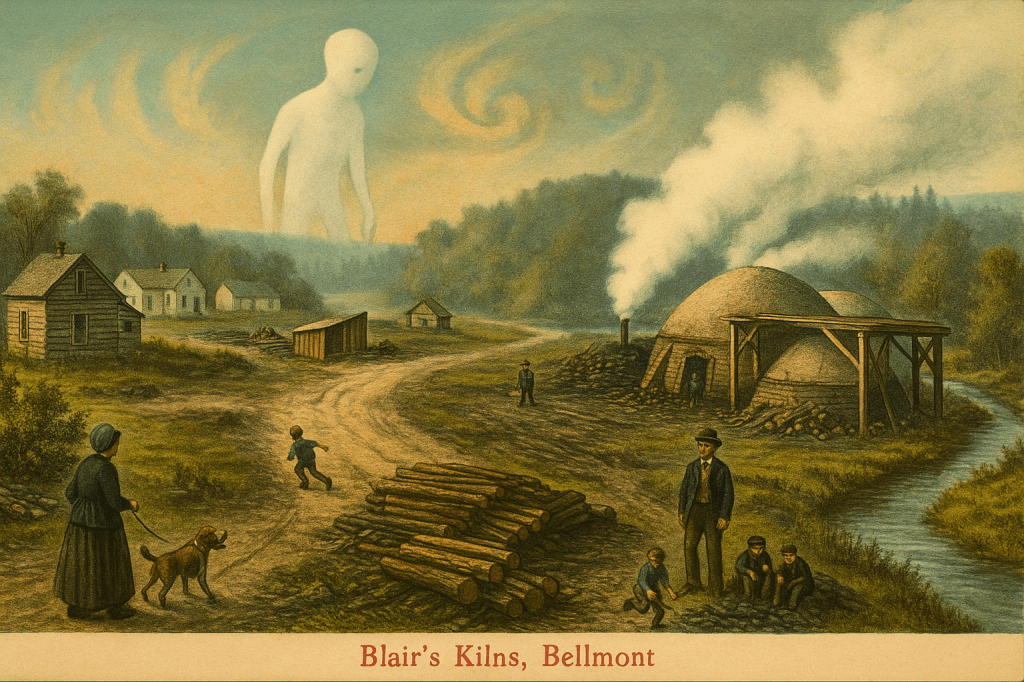

The Blair Kilns—those smoky domes two miles west of Lower Chateaugay Lake, where wood is charred into the iron-belly feed for Pope & Co.’s Forge—have long been cursed by nothing more than damp cordwood and rumors of bootleggers. But in the first week of July, a series of events took place at the Little Trout River crossing that demands accounting beyond the usual tools of fish-weight estimation and barroom conjecture.

Let us begin with the facts. Mr. Fritch was not alone.

Miss Ellie Damp, the widow who keeps a cabbage watch near Mud Hill, was present with her customary cracked Bell jar of lakewater (she claims the water “turns sour when the sky lies”). She witnessed “a rippling of trees—without wind—and a dog-shaped echo that left no paw.” Her remarks were seconded, with some reluctance, by Mr. Tobe Willard, an axe-handle carver known for speaking little and believing less. He merely muttered: “Weren’t any dog I ever seen. Didn’t breathe right. Didn’t blink.”

The beast in question is now being referred to by those inclined to such naming as the Snile-Thing, for it “sniles” (a kind of wet shivering chuckle) and drags its knuckles backwards as though time had wronged its limbs. Its skin, Mr. Fritch claims, was “the precise texture and shade of cured hide left too long in lye,” and its feet moved as though “trying to follow itself through two different yesterdays.”

Nor was this the only creature manifest that week.

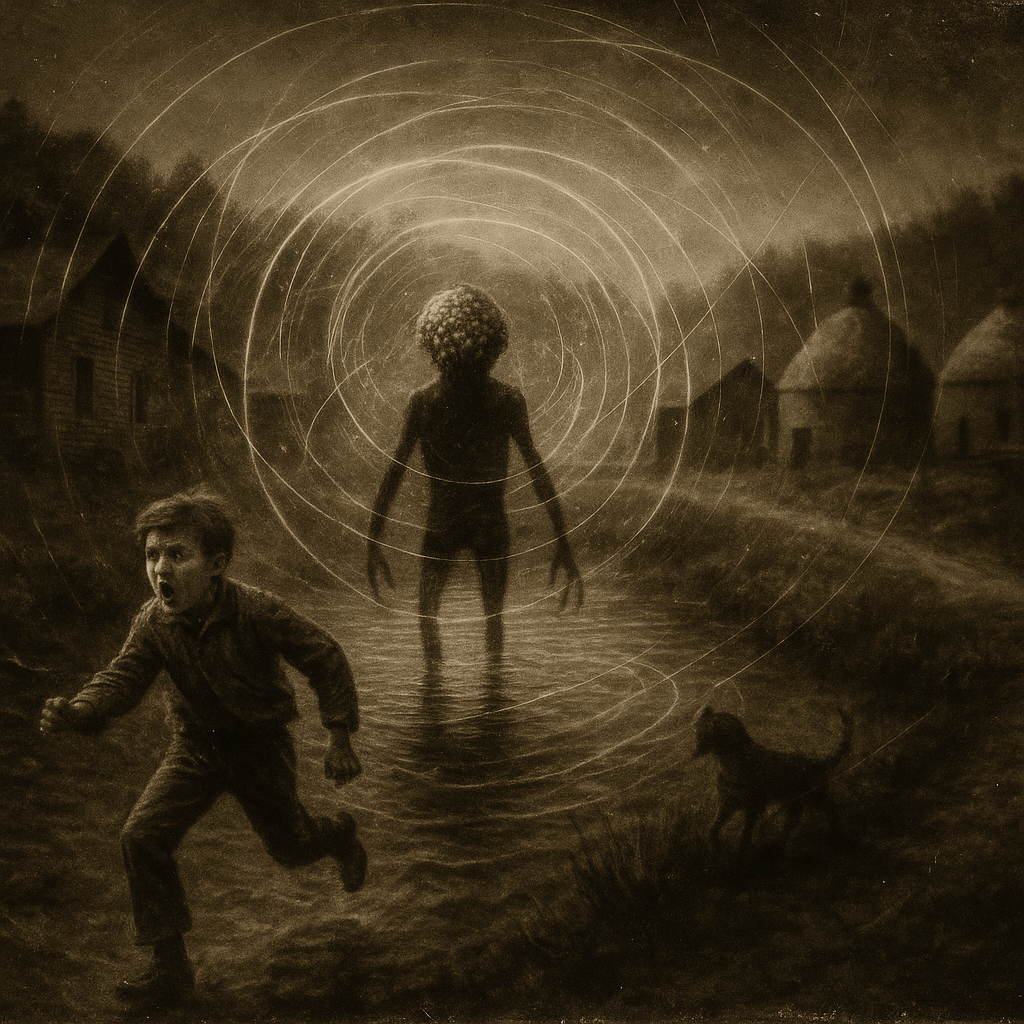

At sundown two days later, young Master Harlan Grigg—a boy whose only known exaggeration concerns the size of perch—fled the river bend near the ash dump screaming of a “High-Faced Meader,” a lank-limbed, shoulderless presence whose head was nothing but a mound of trout scales glinting in unreadable patterns. When found by his uncle, the boy could speak only in numbers for a quarter hour.

A third entity, known now by the forge hands as The Grieve, is said to appear in photographs taken too near the soot piles. The Grieve walks like a drowned woodsman, weeps from no eyes, and according to trapper Claude Sanborn, “turns meat green if it watches you too long.”

A theory has been advanced, primarily by Dr. Ira Thimble—a disgraced electricalist from Saranac currently residing in a chicken coop near Owlyout Creek—that these “beasts” are not beasts at all, but misalignments. “Eddies of form,” he said to no one in particular. “The river there don’t flow forward. It riffs. Like a stuttering reel.”

Thimble, in a half-shaven state, further claimed that the Little Trout’s bend intersects with what he calls a “foam-layer of time-tangency”, wherein certain critters, never quite born, may still be seen—especially in the charcoal smoke cut from Soulia Swamp’s haunted black spruce, puddles, or cracked panes.

We must not dismiss these claims outright. The soil near the kiln-road is known to cough up oddities: eel bones arranged in perfect circles, birds that fall dead only to rise again in reverse order of feathering. The dogs of the region—especially those raised above the marsh-line—refuse to cross the bridge at night. This may mean nothing. But then again, so may a thunderclap before a blue sky.

Skeptics will no doubt suggest mass delusion, or a chemical reaction owing to the charcoal soot. But those who have felt the damp shift in the air above Blair’s No. 4, who have watched a tree stand wrong in its own shadow, or heard laughter where laughter should not come—will know otherwise.

I have seen the black raven of the bog zing low through the smog, changing shape not once but thrice. I have seen footprints where the path was dry, and dry ground where a man fell.

You may believe this or not. But remember—what walks near the Kilns may not be walking here, nor now, at all.

— E. Crandle Brine, Resident Naturalist, East Bellmont Correspondent

Filed with damp hands, and under protest from my own hound

What mysteries of Chateaugay Lake haunt you?